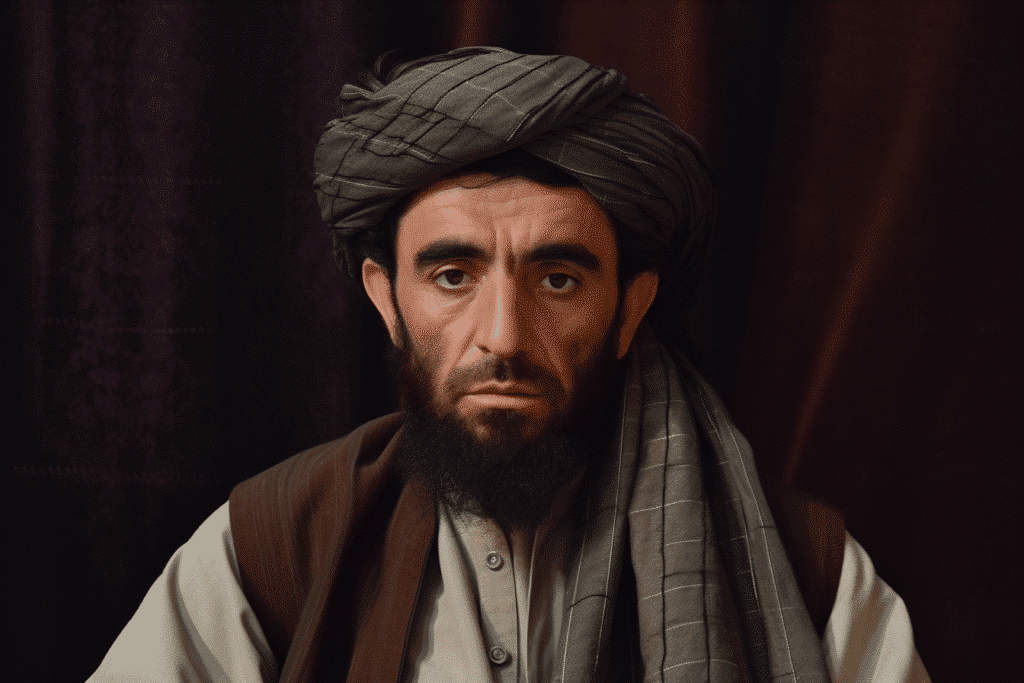

The United Nations (UN) issued a strong critique against the Taliban for implementing public executions, lashings, and stonings in Afghanistan since they seized power. The UN urged the governing body to put an end to such practices.

Over the past half-year, public floggings in Afghanistan have affected 274 men, 58 women, and two boys, as revealed in a report from the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA).

Fiona Frazer, the agency’s top human rights official, stated, “Corporal punishment is a breach of the Convention against Torture and must come to an end.” She also demanded an immediate halt to all executions.

Reacting to the report, the Taliban foreign ministry stated that Afghanistan’s laws are in alignment with Islamic rules and guidelines, which are adhered to by the vast majority of Afghans.

According to the ministry, a conflict between international human rights law and Islamic law must be resolved by following Islamic law.

The Taliban commenced these punishments shortly after assuming power almost two years prior, contradicting initial assurances of more moderate governance than their previous rule during the 1990s.

Concurrently, they have increased restrictions on women, prohibiting them from public spaces, like parks and fitness centers, by their interpretation of Islamic law. These restrictions have sparked an international outcry, exacerbating Afghanistan’s isolation amidst an economic collapse and intensifying a humanitarian crisis.

The report details Taliban practices before and after their August 2021 takeover of Kabul, when U.S. and NATO forces withdrew following twenty years of conflict.

The first public flogging post-Taliban takeover was documented in October 2021 in Kapisa province in northern Afghanistan, where a woman and man were publicly lashed 100 times each on charges of adultery.

In December 2022, the report records the first public execution since the Taliban’s return to power, where an Afghan found guilty of murder was executed.

Carried out by the victim’s father using an assault rifle, the execution in Farah province in the west of Afghanistan was witnessed by hundreds, including high-ranking Taliban officials.

Government spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid said the decision to proceed with the punishment was made with extreme care, following approval from three of the country’s supreme courts and the Taliban’s top leader, Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada.

The report indicates a marked increase in judicial corporal punishment since November, following a tweet by Mujahid endorsing comments by the supreme leader about judges’ application of Islamic law.

Since that tweet, UNAMA has documented at least 43 public lashings involving 274 men, 58 women, and two boys. The majority of these punishments stemmed from convictions of adultery and desertion. Other alleged offences included theft, homosexuality, alcohol consumption, fraud, and drug trafficking.

In a video message last week, Taliban deputy chief justice Abdul Malik Haqqani reported that the Taliban’s Supreme Court had issued 79 floggings and 37 stonings since taking power.

Following their initial defeat by the 2001 U.S. invasion, the Taliban continued to implement corporal punishment and executions in areas they controlled while fighting the U.S.-backed former Afghan government, according to the report.

Despite many Muslim-majority countries incorporating Islamic law, the interpretation by the Taliban is viewed as an outlier.

The Taliban’s ban on women working has been condemned as a flagrant violation of Afghan human rights by U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

On April 5, Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers informed the United Nations that Afghan women working for the UN mission could no longer report to their jobs. This move has raised concerns among aid agencies, who warn that the prohibition on women’s employment will hinder their ability to provide much-needed humanitarian aid in Afghanistan.

The Taliban has previously barred girls from receiving education beyond the sixth grade, primarily excluding women from public life and work. In December, they extended the ban to Afghan women working for local and non-governmental organizations, although the restriction did not apply to U.N. offices then.

It was routine practice for individuals convicted of crimes to be executed in large public areas, such as sports stadiums and intersections, during the first Taliban regime from 1996 to 2001.

As the current Taliban regime continues to enforce a stringent interpretation of Islamic law, the international community looks on with increasing concern. Human rights groups and the United Nations continue to advocate for a cease to these practices, while Afghan citizens bear the brunt of these harsh measures. The challenge remains to balance respecting a nation’s cultural and religious autonomy and upholding its citizens’ basic human rights and freedoms.