Once a poacher in Nigeria’s Omo Forest Reserve, Sunday Abiodun now shoulders the responsibility of conserving it. With a sword and musket, he clears a path to freshly planted trees, replacing areas where cocoa crops once stood.

Cocoa farming had previously led to deforestation in the reserve, impacting bird populations. Abiodun and his fellow rangers now rehabilitate these areas. “On patrol, when we encounter such farms, we replace them with trees,” he says, hopeful that in a decade, these trees could alleviate biodiversity losses.

Abiodun’s transformation from a poacher, who once hunted endangered species like pangolins, to a guardian of the forest is emblematic of a broader shift. He and others now safeguard the Omo Forest Reserve against threats like over-logging, unregulated farming, and poaching.

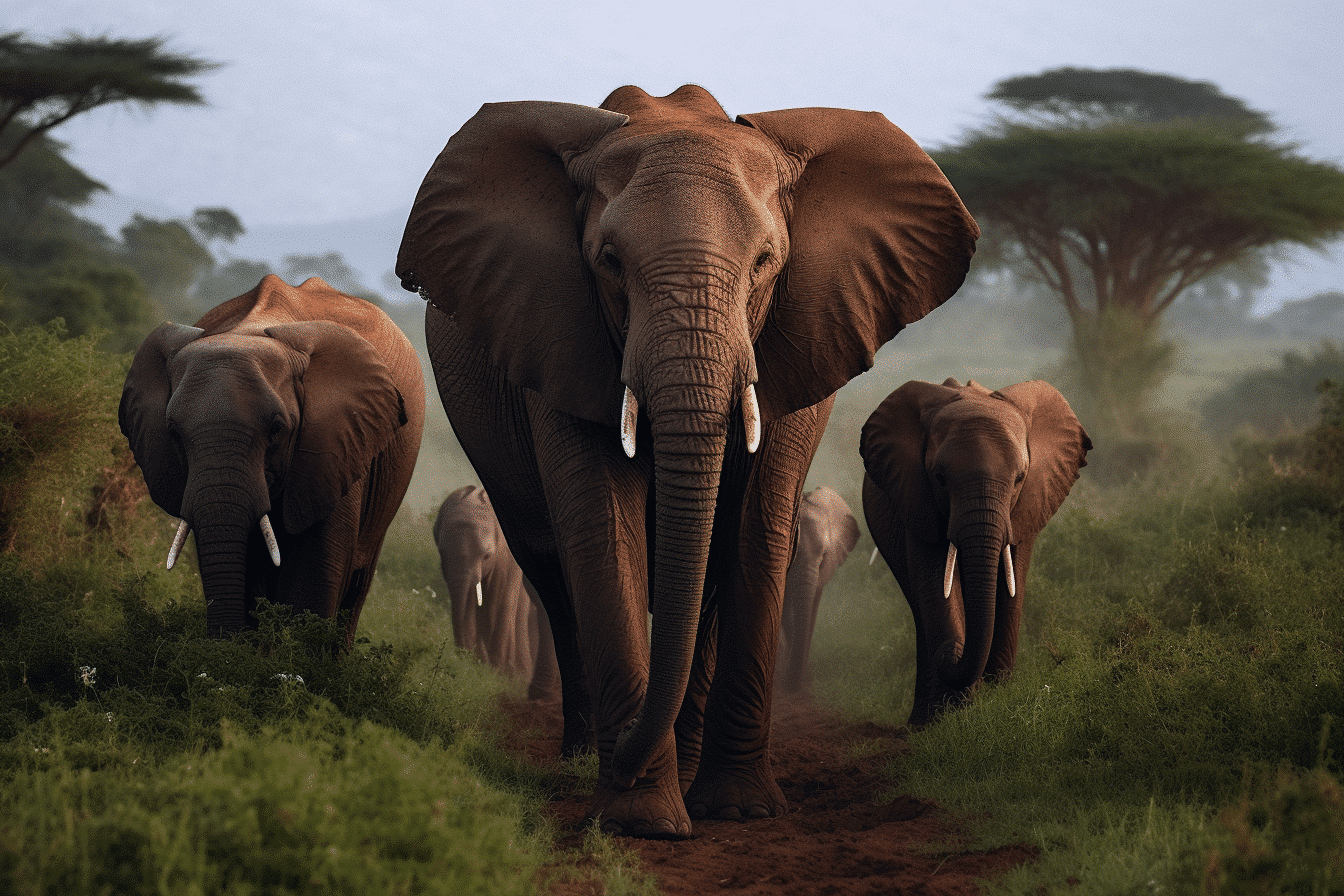

Located 135 kilometres northeast of Lagos, this tropical rainforest shelters threatened species, including forest elephants, pangolins, and chimpanzees. Over 40% of this forest, approximately 550 square kilometres, is now a designated conservation area, according to Emmanuel Olabode of the Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF).

A particular area of concern is the 6.5 square kilometre UNESCO-designated Biosphere Reserve, believed to be home to elephants. Olabode emphasizes the rangers’ critical role: “This could be the last sanctuary for forest elephants in Nigeria. If lost, the elephants might disappear.”

Engaging former hunters in conservation has been transformative, especially in anti-poaching efforts. Memudu Adebayo of NCF explains that converting leaders from the hunting community brings not just one individual but influences others to join the cause.

This change in vocation gave Abiodun a fresh perspective. In his earlier days, he’d see people visiting the forest, keen to learn about the very wildlife he was hunting. “I pondered,” he recalls, “what if my own children wish to see these creatures in the future?”

This shift offers tangible benefits. “They now have a consistent income while positively impacting the environment,” Adebayo adds.

Innovations, like installing motion-activated cameras, help monitor both wildlife and potential poachers. But the fight isn’t over. Illegal cocoa farming and logging continue to be significant challenges, as Johnson Adejayin, another converted ranger, notes, “Those arrested often return to continue illicit activities.”

Rangers urge local communities to participate in reforestation but stress that governmental enforcement is essential. The forest’s degradation is of significant concern to ecologists like Agboola, who says, “As trees fall, we’re not just losing biodiversity but also vital solutions to combat climate change.”

The metamorphosis of hunters like Abiodun and Adejayin into stewards of the Omo Forest Reserve highlights the potential for change when individuals recognize the broader implications of their actions. The combined efforts of rangers, communities, and conservation organizations are a testament to the belief that it’s never too late to pivot and prioritize the environment. For Nigeria’s Omo Forest, its rich biodiversity, and the generations that will come after, such transformations are not just inspiring but essential. Together, they weave a tale of hope, redemption, and shared responsibility.