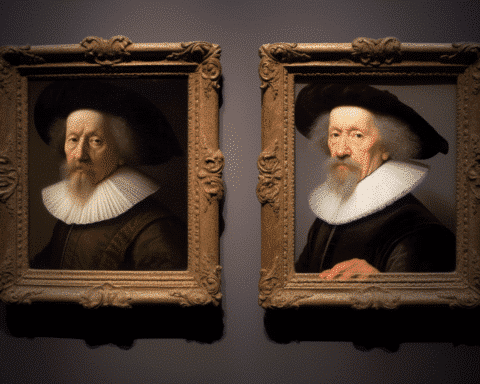

In an age where digital filters and cosmetic enhancements are the norms, a fascinating discovery by English Heritage serves as a reminder that altering appearances is not solely a contemporary practice. The recent restoration of a 17th-century portrait of noblewoman Diana Cecil has unveiled a centuries-old practice of image touch-ups. This restoration project not only reveals the true features of Cecil, a figure of historical significance but also uncovers intriguing aspects of art history and conservation.

English Heritage, the custodian of over 400 historic sites in England, embarked on this meticulous restoration of Diana Cecil’s portrait. Cecil, who lived from 1596 to 1654, was a member of a powerful family at the Jacobean court, the great-granddaughter of William Cecil, Lord Burghley, an influential advisor to Elizabeth I.

The portrait, previously altered to enhance Cecil’s appearance, underwent significant restoration. Conservators painstakingly removed the changes to her lips and hairline, revealing her natural features. These alterations, believed to have been made in the late 19th or early 20th century, were possibly intended to cover damage from the rolled portrait, causing significant harm.

Another revelation was the discovery of the artist’s signature, Cornelius Johnson, and the date 1634, hidden behind a curtain in the painting. This finding predates four years of the previously believed date of the portrait’s creation.

Alice Tate-Harte, Collections Conservator (Fine Art) at English Heritage, expressed her amazement at the restoration’s outcome. “As a paintings conservator, I am often amazed by the vivid and rich colours that reveal themselves as I remove old, yellowing varnish from portraits, but finding out Diana’s features had been changed so much was certainly a surprise,” she said. Tate-Harte’s commitment to restoring the portrait’s originality is a testament to the importance of preserving historical authenticity.

The unveiling of Diana Cecil’s true likeness is more than just a painting restoration; it is a restoration of historical truth. The updated portrait, to be displayed at Kenwood House in London alongside a picture of her husband, Thomas Bruce, the 1st Earl of Elgin, is a window into the past. It reminds us of the enduring human desire to portray beauty, the complexities of art conservation, and the significance of preserving our cultural heritage in its most authentic form.