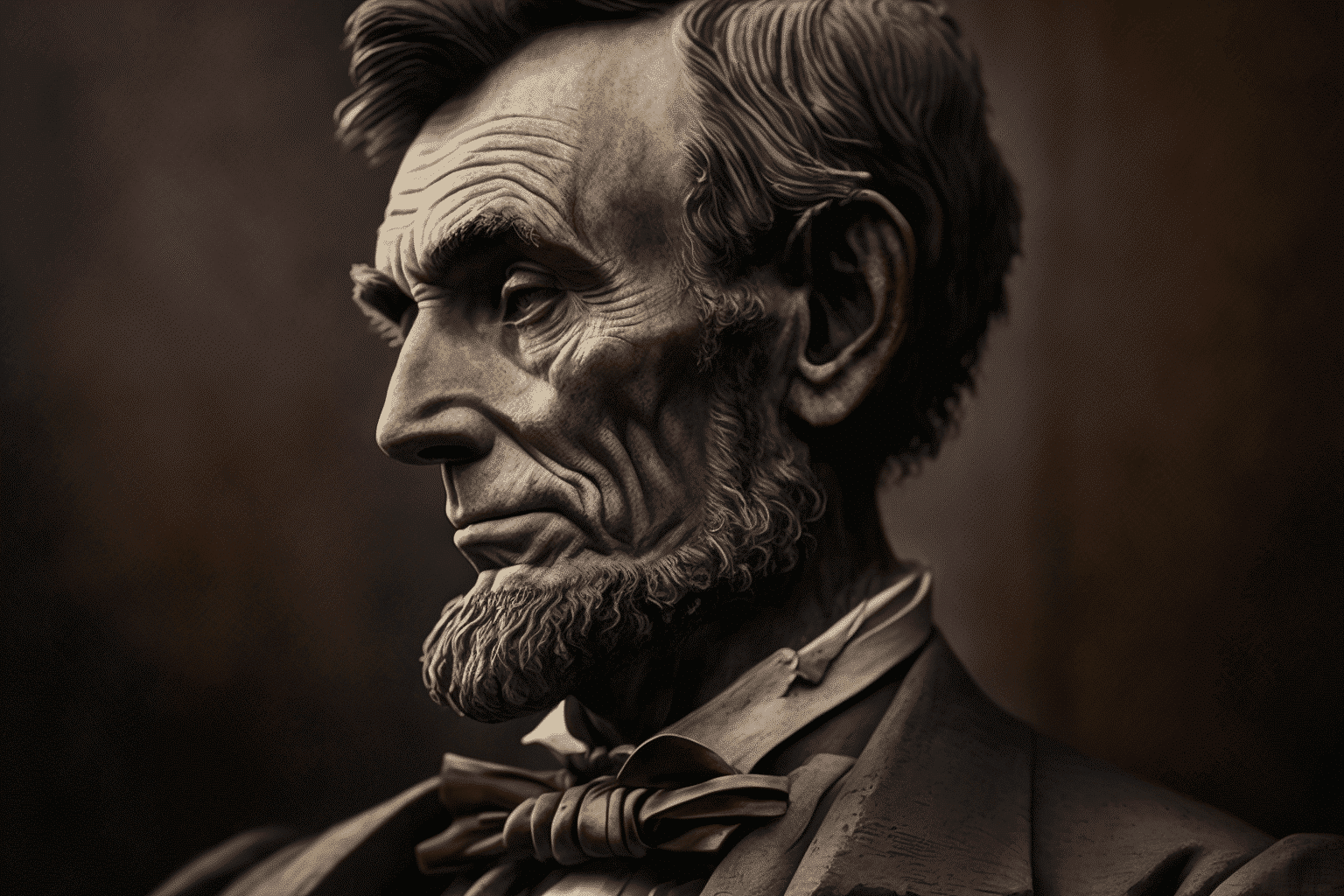

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. has recently acquired a life-size portrait of Abraham Lincoln, painted by Dutch artist W.F.K. Travers in 1865.

The 9-foot tall painting debuted at the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia and was praised for its realism and likeness to the 16th president.

After being displayed at the exhibition, the painting was nearly burned and eventually hung in a New Jersey borough council chamber for 80 years before it was restored and returned to the National Portrait Gallery.

The painting is part of the museum’s “America’s Presidents” exhibition and is the only site outside the White House to hold portraits of all U.S. presidents.

The Lincoln portrait is reunited with Gilbert Stuart’s famous Lansdowne portrait of George Washington, also displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition.

The restoration of the painting reveals various symbolic elements, including glimpses of George Washington and a globe turned towards the Caribbean, and a black glove on the floor, which may symbolize mourning.

The painting’s return to the Portrait Gallery is significant as it was in the same building where Lincoln applied for and received a patent for a boat floatation device. A full-size digital reproduction of the painting has also been installed in Madison, New Jersey.

After many years of being lost, the life-size portrait of Abraham Lincoln has found a new home at the National Portrait Gallery.

Museum Director, Kim Sajet, expressed her excitement at the painting’s arrival, stating that it is perfectly located next to the famous Gilbert Stuart Lansdowne portrait of George Washington.

The reunion of these two portraits, as they were displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, highlights the museum’s ongoing ‘America’s Presidents’ exhibition.

The National Portrait Gallery is the only place outside the White House that holds portraits of all US Presidents.

The painting had a tumultuous journey before finally reaching the National Portrait Gallery. After the 1876 exhibition, it was nearly burned and stored at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where it almost met its end in a storage fire.

It was then considered an orphan in Washington and hung in various places, such as a hotel window and a naval subcommittee room in the US Capitol.

In the 1920s, the Rockefellers became its owners and placed it in the Hartley Dodge Memorial in Madison, New Jersey.

When the painting was restored in 2021, it was revealed that it had been covered in a thick yellow varnish, which may have protected it from decades of smoking in the council chambers.

The restoration and expert lighting at the Portrait Gallery bring out the many symbolic elements in the painting, including glimpses of George Washington, the Constitution, and a mysterious black glove on the floor.

The painting also features a globe pointing towards Haiti or Honduras, where the artist had spent his childhood. The painting is one of the few portraits in the ‘America’s Presidents’ gallery that the museum does not own.

The restoration of the painting has revealed many hidden details and raised new questions about its creation.

The painting was likely created between the passage of the 13th Amendment in January 1865 and Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, and it is believed that Lincoln may have posed for the painting, though there is no proof.

The painting is now displayed alongside a haggard portrait of Lincoln from 1865 and a tactile display for the visually impaired, which includes replicas of a Lincoln face mask and hands.”

The completion of the Lincoln portrait by Francis B. Carpenter must have occurred between the passage of the 13th Amendment on January 31, 1865, and his assassination on April 15, 1865, excluding the two weeks Lincoln visited Richmond after the city’s fall in spring.

It remains to be seen whether Lincoln sat for the painting, one of three known full-length portraits of the president. “While we believe he did, we don’t have any proof,” said Widmer, adding that White House records from the period are incomplete.

The portrait is unique compared to other memorial paintings done after Lincoln’s death as it doesn’t show any signs of mourning, according to Schöberlein.

“Perhaps the dropped glove, which may have been a later addition, is a subtle way of acknowledging his passing,” he said.

“The mysteries surrounding this painting just keep deepening,” said Widmer, “and it has been a thrilling experience for me as a historian.”

Sajet noted that Lincoln’s return to the National Portrait Gallery building holds special significance, as it was in these halls when it was the U.S. Patent Office that Lincoln applied for and received a patent for a device intended to free boats from sandbars.

The Greek Revival building, which spanned an entire block and was given to the Smithsonian by Congress in 1962, was also the site of Lincoln’s second inaugural ball held in 1865, a month before his death.

The Lincoln portrait is one of several in the “America’s Presidents” exhibition that the museum does not own.

The portraits of Andrew Jackson by Thomas Sully, Martin Van Buren by George Peter Alexander Healy, Benjamin Harrison by Theodore Clement Steele, and Dwight D. Eisenhower by Thomas E. Stephens are all from private collections or lent by the White House, Purdue University, and Eisenhower’s Presidential Library, respectively.

The Lincoln portrait is now displayed alongside the haggard portrait of the president in a February 1865 photograph by Alexander Gardner and a tactile display designed for the visually impaired, which includes three-dimensional replicas of a face mask and hands cast by Leonard Volk in 1860 and Clark Mills in 1865.

A full-size digital reproduction of Travers’ painting has also been installed in Madison, New Jersey, where the original painting once hung, according to Anne MacCowatt, a trustee of the Hartley Dodge Foundation.

“The borough was worried they would be without the painting, so we promised to make it up to them,” she said. “I believe we have succeeded in our mission.”