Over ten years ago, Matika Wilbur embarked on a journey to capture the essence of all 562 federally recognized Native American tribes in the United States, a figure that has now increased to 574. Her goal was to compile a representative image of modern Indigenous life that would dispel enduring stereotypes while positively influencing the newest generation of Native Americans.

Wilbur’s mission, Project 562, was centred around narrative correction. “When I first started, my focus was on revealing the face of modern Indigenous identity, on truly capturing what it means to be a Native individual today,” she shared during a video conference.

Wilbur hadn’t anticipated how deeply her project, which has now culminated in the recently published book “Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America,” would influence her journey. A member of the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes of the Pacific Northwest, Wilbur resided in Seattle in 2012, just before the start of her project. As her journey concluded, having covered 450,000 miles, Wilbur became pregnant and decided to return to her home in Tulalip with her husband.

“I felt a strong pull to return home so that my child could form a connection with this land,” Wilbur explained. “I wanted her afterbirth to be buried here, under her grandmother’s cedar tree, among her ancestors. This realization struck me as incredibly significant.”

Project 562 is remarkable in its ambition, featuring tribes ranging from the Miccosukee Tribe in the Everglades to the Siberian Yupik people off the coast of Alaska.

The portraits—encompassing elders, teenagers, and multi-generational families—radiate warmth and intimacy, complementing each image with the subjects’ narratives. The project explores kinship, love, displacement, reconnection, the enduring effects of colonialism and racism, environmental justice, activism, and a sense of belonging.

As the project evolved, Wilbur was transformed by the work, deepening her understanding of her connection to the land of her upbringing.

“We have systematic ways of teaching our children to form bonds with their homeland and to become its caretakers,” Wilbur said. “As I began my travels, I started to recognize and appreciate the diverse ways different communities practiced this. It felt natural to me since my upbringing included fishing, canoeing, attending ceremonies at the longhouse, and other activities that connected me with the tides. However, I wouldn’t have recognized these influences a decade ago.”

The more she journeyed, the more she realized her identity’s “site-specific” nature. “I met people of the blue-green waters, of the tall pine trees, of the four sacred mountains, and I participated in their ceremonies and observed cultural protocols that deeply connected them to their land. This realization was profound for me.”

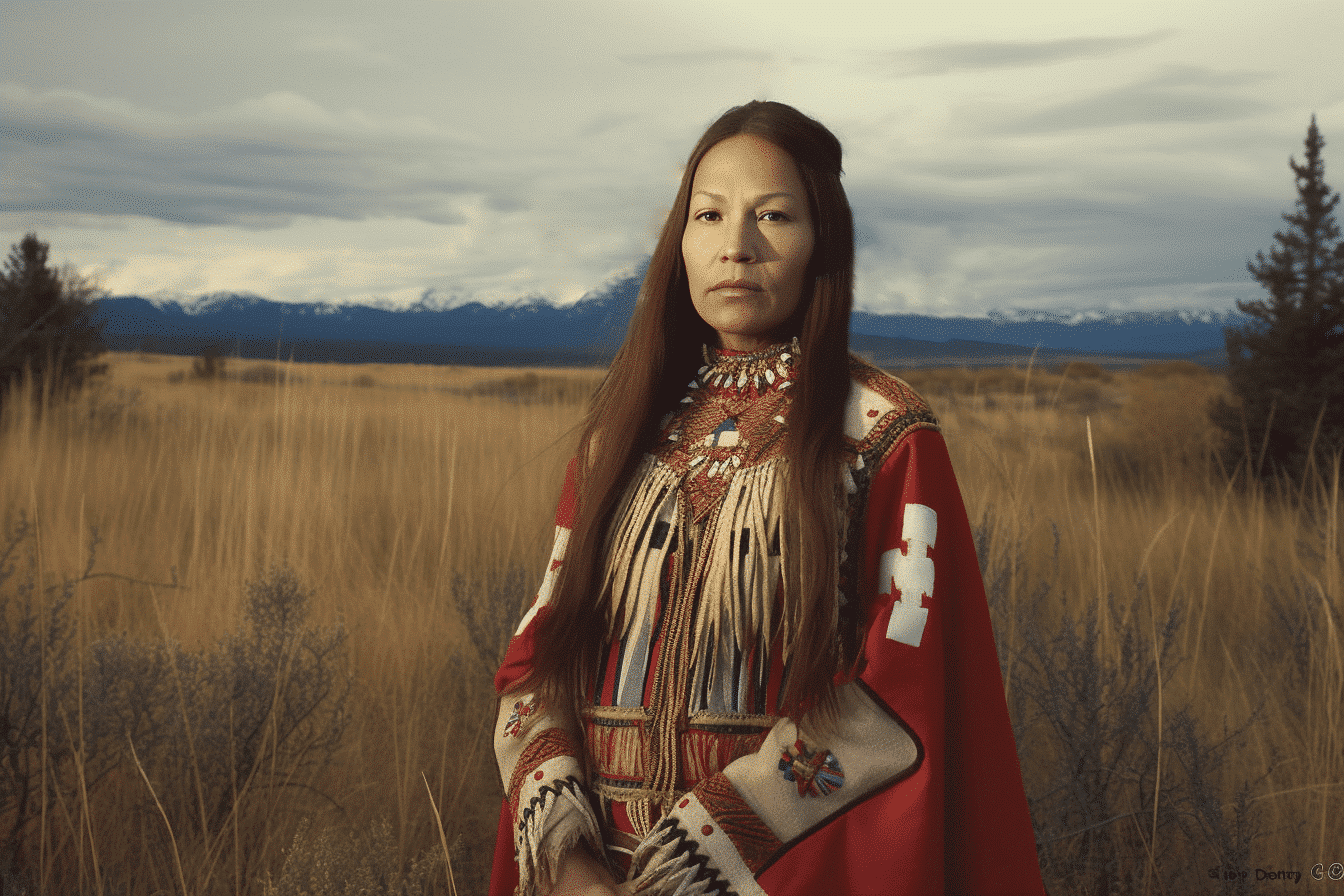

Below are some featured portraits from “Project 562,” along with the stories behind them.

Dr. Henrietta Mann

CHEYENNE

Dr. Henrietta Mann, an educator for over five decades who helped shape Native American studies programs at several universities, was recently awarded a National Humanities Medal by President Biden. She graces the cover of “Project 562.”

“I wanted a matriarch on the cover,” Wilbur told CNN. “I’ve given a lot of thought to repatriation (restoring sacred principles) and how crucial it is to uplift women who, like Auntie Dr. Henrietta Mann, have dedicated their lives to improving the lives of Indigenous people.”

Hannah Tomeo

COLVILLE, YAKAMA, NEZ PERCE, SIOUX, SAMOAN

An athlete and a Northwest Indian Youth Conference Princess, Hannah Tomeo, was photographed in Methow Valley during the conference. At the 2016-2017 event, Tomeo and Wilbur were keynote speakers.

Tomeo shared her story with Wilbur: “Running has always been my passion and rock. However, during high school, I felt nobody wanted me to succeed. My teacher told me it was in my genes to become an alcoholic; my basketball coach singled me out for drug tests; my track coach told me I would be another hopeless Indian runner. I let these words drive me until I had the fastest times in the school, but they still wouldn’t let me race.” Tomeo was taken out of races without reason until she eventually quit. “My spirit was completely shattered. I thought I would never run again. But then, my father told me, ‘You can either be a quitter or come back a success story. Your choice.’”

“I trained harder than ever that summer and made a strong comeback. I made it to the State competition, made the first team, and placed in the Nike meet in Boise and Footlocker in California… My story isn’t over yet.”

Darkfeather Ancheta, Eckos Chartraw-Ancheta, and Bibiana Ancheta

TULALIP

Darkfeather and Bibiana Ancheta, who Wilbur refers to as “like sisters,” are pictured here with Bibiana’s son, Eckos.

“I had a dream about them standing in front of Tulalip Bay like in this photograph,” Wilbur told CNN. “So I called them and asked them if I could capture the image I had seen in my dream.”

“We have these kinship systems and familial ties in our communities where an aunt is like a second mother. She is a protector and equally invested in the child’s upbringing… I aimed to capture the essence of our care and love for our children in this image.”

Joshua Dean Iokua Ikaikaloa Mori

KĀNAKA MAOLI

Joshua Mori, a farmer, teacher, and founder of community, wellness, and agriculture nonprofit Iwikua in Kauaʻi, Hawaii, is pictured with one of his three children on his aquaponic farm.

“My work is about reclaiming our food system and combating colonialism at its root,” Mori told Wilbur for “Project 562.” “Our diet, which affects everything from our feelings and thoughts to love and procreation, is the root source. That’s why we’re practicing aquaponic farming, a traditional food system adapted to modern technology. We integrate our traditional Native knowledge with modern technology to make it more accessible.”

“The kids learn traditional house building, traditional farming, working in kalo patches, and modern farming techniques when they come here,” he added. “They also learn how to spearfish and fish traditionally and star navigation. Essentially, they learn to use all the tools that made Hawaiians who they are.”

Drew Michael

YUP’IK, IÑUPIAQ

Drew Michael, a traditional Yup’ik mask-maker who identifies as Two Spirit, was adopted and raised by non-Native parents in Alaska. He spoke with Wilbur about his journey to reconnect with his Indigenous identity and was photographed in his home.

“Growing up, I did not have a strong sense of my culture or identity as a Yup’ik and Iñupiaq man… I only gained access to it when I took a carving class with my father,” Michael shared with Wilbur for “Project 562”. “Creating my piece, a replication of a mask from an exhibition book, was my first introduction to my culture. From that point, I felt like I was starting to claim it. As I delved more into the purpose and use of masks, the ceremonies, and rituals, I started to learn about myself through the masks.”

“In Yup’ik culture, Two-Spirited individuals were typically healers because they could connect with both masculine and feminine worlds. Since I identify as Two-Spirited and create masks, I aim to discuss different forms of healing within my work.”

Fannie and Robert Mitchell

DINÉ

Married for over six decades, the Mitchells’ lives are deeply rooted in their traditional Navajo lifestyle. Robert, a former railroad worker, now tends to livestock on their land. As they prefer to communicate in Navajo, their daughter-in-law served as a translator for Wilbur. Wilbur celebrated her 30th birthday with them, enjoying dinner, cake, and gifts at their home.

“It’s rare to meet Native people who solely speak their language. So, for me, it was a profound experience to be in a home where they live very traditionally, care for sheep, and speak their language,” Wilbur shared with CNN.

“During my journey, I approached it in the only way I know — as a Native person. I never arrived empty-handed, brought food, and stayed a while. I left traditional gifts behind and stayed in touch with folks, so I felt fortunate to meet them and spend some time in their home.”

She added there was a touch of chaos just outside the frame. “A wider shot of this portrait would show a sheep licking me as I’m taking this photo and two horses trying to eat my light… and that’s why they’re laughing.”

John Sneezy

SAN CARLOS APACHE

Identifying as Two Spirit, John Sneezy was a Grass Dancer at powwows for over three decades. He could not perform in the Traditional Cloth category — which Wilbur notes is danced by women — until 2016 when he participated in the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit Powwow (BAAITS). Wilbur photographed him in San Francisco. He passed away before the book’s publication.

“Young Two Spirit individuals in Indian Country face a lot of violence due to their identity. John would say, ‘I dance, and I wear women’s regalia, and I want to be shown in your book like this,’” Wilbur recalled to CNN. “John called me and emphasized how important it was to continue to elevate stories about Two Spirit people so that our young Two-Spirit relatives feel safe, seen, and heard.”

“John had spent his whole life wanting to dance in a woman’s Apache dress but didn’t feel safe until he travelled to the Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit Powwow. This speaks volumes about how members of the LGBTQ+ community are treated in some of our communities. In national conversations about Indigenous identity, we must acknowledge our Two Spirit relatives and create space for representation. John would want me to share Wilbur’s powerful and intimate portraits in “Project 562,” which reflect the richness, diversity, and resilience of Native communities across the United States.

Her work is a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples and a timely reminder of the importance of representation and visibility in contemporary conversations about identity and culture. By providing a platform for the stories and voices of individuals often overlooked in mainstream narratives, Wilbur has highlighted their distinct experiences and underscored their invaluable contributions to the fabric of American life.