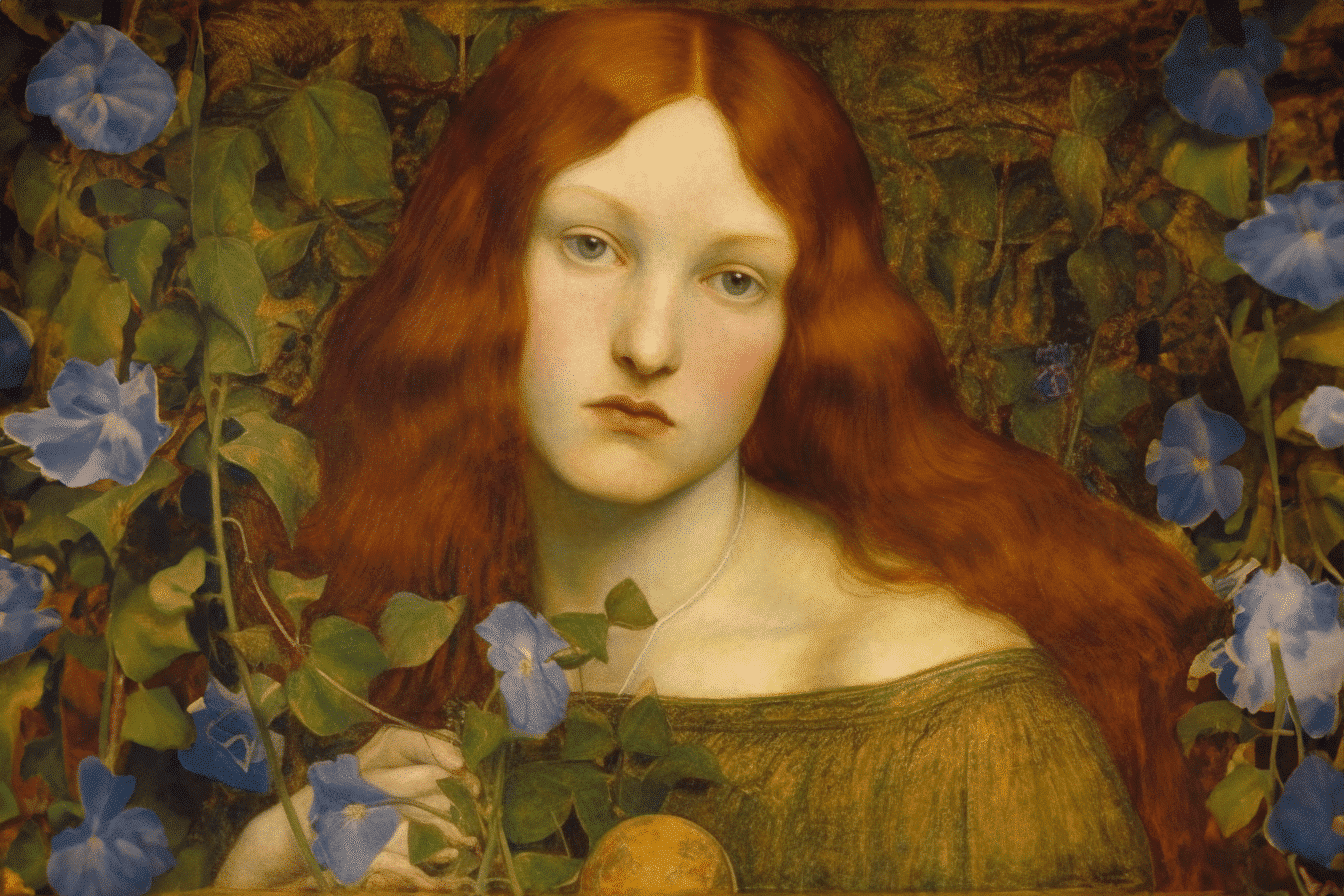

Elizabeth Siddal might be a name you’re unfamiliar with, yet the iconic 19th-century paintings she posed for are likely embedded in your cultural memory. Siddal is immortalized in portrayals of tragic scenes, whether she’s Ophelia submerging in a flower-adorned riverbank or Dante Alighieri’s dying beloved, bathed in the radiance of rapture. Siddal’s poignant tale is often narrated, hinting at her tumultuous romantic relationships, delicate health, and untimely death at 32 due to laudanum intoxication.

Yet, what often goes unacknowledged is Siddal’s significant contribution as an artist and poet. Her vivid, emotionally evocative artwork and heartfelt ballads represent a remarkable facet of her life. The Tate Britain’s latest exhibition in London, “The Rossetti,” is partly aimed at rectifying this oversight. The show primarily spotlights Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Siddal’s husband, his sister and poet Christina, and Siddal herself, showcases over 30 of Siddal’s works, marking the largest assembly in 30 years.

As the sole woman to display work in the ephemeral yet highly romanticized Pre-Raphaelite movement, Siddal was recognized for her modelling for artists like Rossetti and John Everett Millais. However, scholars and curators are now focusing on her infrequently exhibited surviving artwork, which consists of approximately 60 works on paper and a few paintings.

According to Carol Jacobi, the Tate curator, both the physical frailty and a limited number of Siddal’s works have resulted in her receiving less exposure. “And we cannot deny that, particularly for historical women artists, it’s still a bit of a battle,” she noted.

Siddal’s art was known for departing from realism, embracing beauty and fantasy. Her artistic creations often encapsulated emotionally intense scenes from poems. Most of her artwork comprises watercolours and sketches, with her only known oil painting – a gently portrayed self-portrait on a circular canvas – lost in the annals of time.

The need for a more balanced representation of Siddal as an influential artist in her own right, rather than an appendage to her male counterparts is long overdue. Institutions are increasingly adopting this shift for renowned “muses” of art history, such as photographer Dora Maar, famously Picasso’s “Weeping Woman,” and painter Suzanne Valadon.

However, acknowledging Siddal’s significance has been a convoluted process. Jan Marsh, a curator and scholar, has advocated for Siddal’s crucial role in the Pre-Raphaelite movement since the 1980s. Yet, distorted myths and misunderstandings about Siddal endure.

TV and film portrayals have continued this skewed narrative, exemplified in the 2009 BBC miniseries “Desperate Romantics” and the 1967 drama “Dante’s Inferno.” The film, directed by Ken Russell, starts with Siddal’s exhumation, further perpetuating the myth of Siddal as a “haunted woman.”

Siddal’s true legacy exceeds these oversimplified narratives. Despite being largely self-taught, she was not simply discovered while working in a hat shop, as myths suggest. Moreover, her health struggles and opiate addiction have probably been overstated.

Her death, often presumed to be suicide, is largely misunderstood. Marsh asserts that Siddal likely succumbed to an opiate overdose during a post-partum psychosis following a stillbirth, but concrete evidence of her being an addict is lacking.

Although many historians have downplayed Siddal’s work as merely being influenced by her husband, Jacobi believes that their work was more collaborative, with Rossetti drawing as much from her.

Siddal’s visionary approach might have been more appreciated if she had lived to witness the next wave of art — one she unknowingly influenced.

Jacobi, through “The Rossettis,” aims to present the true story of Siddal: A woman from a working-class background who dared to become a painter and poet in a time when her gender and class status were severe constraints. Mainstream institutions primarily unacknowledged her work, and she even defied their preferences.

In Jacobi’s view, “She was painting in (her) own way… largely self-taught — that is the story of a modern artist. And I think she was just 30 years before her time.”

The world was introduced to Elizabeth Siddal through the masterpieces she inspired, but the time has come to appreciate her contributions to the art world. As the narrative shifts from her role as a muse to her prominence as a trailblazing artist, we get a glimpse of a woman ahead of her time, making her mark on the canvas of history. Through her pioneering artwork and poetry, she invites us to explore beyond the frame of her portraits and discover her authentic self.