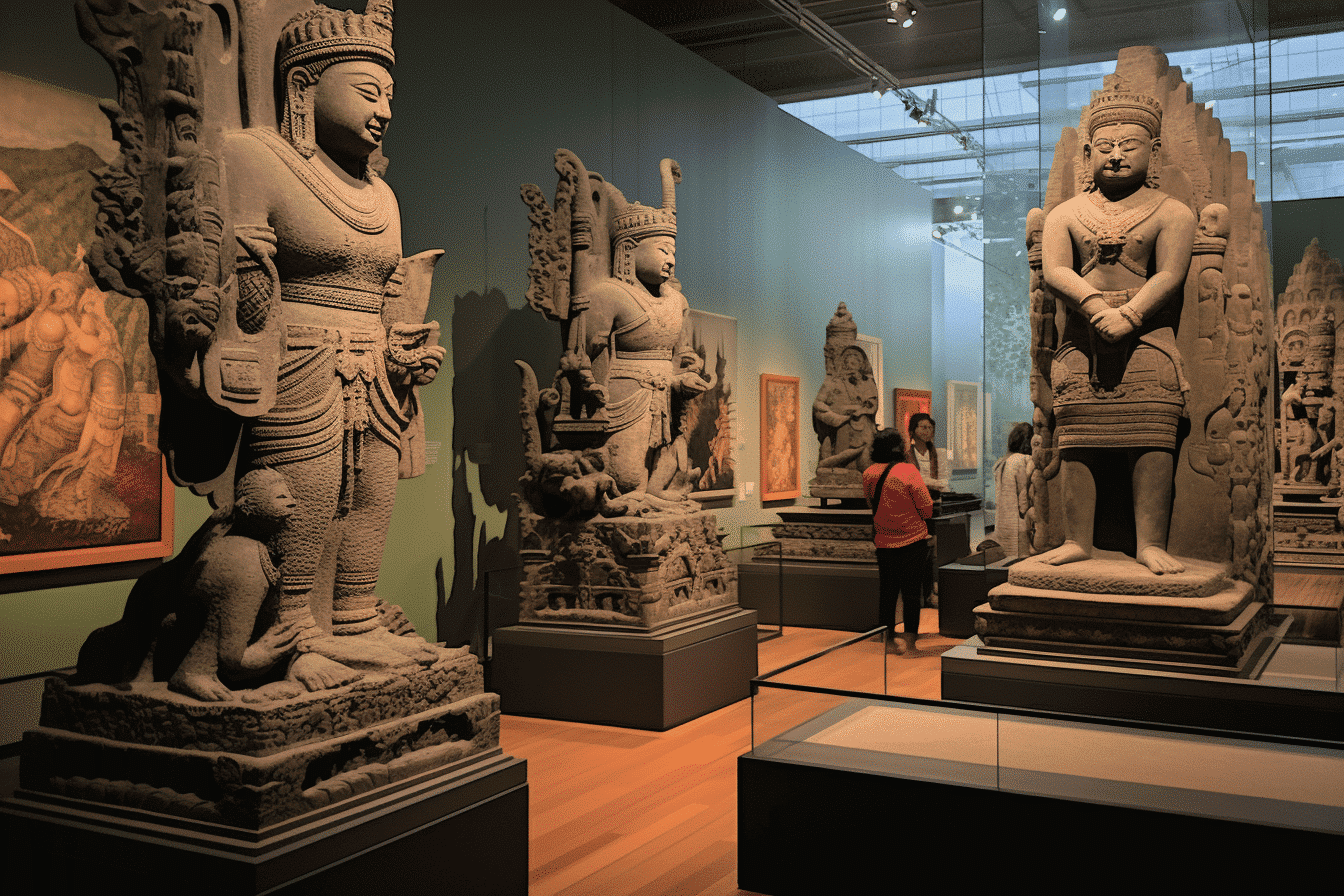

The Dutch administration is set to send back 478 items seized during colonial rule to Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

In response to multiple claims filed by Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Nigeria, Gunay Uslu, the Dutch Secretary of State for Culture and Media, declared on Thursday the decision to repatriate items such as the “Lombok treasure”, which includes 335 objects from Lombok, Indonesia, the Pita Maha collection, a significant collection of modern art from Bali, and the 18th-century Cannon of Kandy, a Sri Lankan ceremonial weapon made of bronze, silver, and gold and studded with rubies.

“This marks a historic occasion,” stated Uslu in a press release. “It’s the first instance of us following suggestions… to return items that should have never been brought to the Netherlands. But more importantly, it’s a time to look forward and focus on the future. We’re repatriating items and starting a phase of enhanced collaboration with Indonesia and Sri Lanka in areas such as collection research, exhibit presentations and museum exchanges.”

A report from the Dutch Council for Culture in 2020, chaired by human rights attorney Lilian Gonçalves-Ho Kang You, proposed that the nation should “unconditionally” return items it could reasonably ascertain were involuntarily lost by countries under its colonial governance.

Most items slated for return are currently housed in the National Museum of World Cultures. Six additional colonial artifacts claimed by Sri Lanka are in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, the Dutch national museum of arts and History. This is the inaugural repatriation of such artifacts from this museum, following provenance research that commenced in 2017. For example, the Cannon of Kandy was seized by the Dutch East India Company’s troops during the 1765 sack and plunder of Kandy and was later gifted to William V, Prince of Orange.

Valika Smeulders, the head of the history department at the Rijksmuseum, told The Art Newspaper that there’s been a noticeable shift in attitude.

“Museums, particularly those in Europe, were concerned about preserving objects for future generations, and this dominated much of the 20th-century debate,” she remarked. “However, our perspective has evolved: these objects are meant to narrate the histories of our nations, our intertwined histories. We now see our mission as placing these objects where they can best recount the relevant stories.”

Smeulders dismissed the fears that the new policy could result in European museums losing collection highlights, which until recently were factors in deciding on restitution claims of art looted by the Nazis in the Netherlands.

“I don’t truly believe that’s going to happen because I anticipate discussions between the countries of origin and European museums about which items should be repatriated, and it won’t be all of them,” Smeulders added. “We will all gain deeper knowledge about these items, how they came into our possession, their history, and the stories they can tell. So, in the end, our work will be enriched, not galleries left empty.”

The collection of objects to be repatriated to Indonesia will not include the “Java man” human remains displayed at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden and among the earliest specimens of the extinct early human, Homo erectus.

On Thursday, a representative for the Dutch government told The Guardian that a decision concerning the “Java man” remains is still pending.

“Nothing has been rejected, but some decisions take more time than others,” the spokesperson commented.

Gert-Jan van den Bergh, an art law specialist at Bergh Stoop & Sanders, stated to The Art Newspaper that the repatriation effort was “a significant initial move, but merely a first step.”

“Keep in mind, the Dutch state alone possesses 300,000 colonial objects,” Van den Bergh said, adding that there should be more examination of privately-owned colonial objects, including those in major auction houses.

A ceremonial handing over of objects to the National Museum of Indonesia in Jakarta will be held at the Museum Volkenkunde Leiden.

This move signifies a turning point in recognizing and correcting historical wrongs as countries like the Netherlands grapple with their colonial pasts. The repatriation process might serve as a blueprint for other nations that hold looted artifacts from former colonies, advocating a more equitable global cultural exchange and respectful treatment of historical objects. As these repatriated objects find their way home, they will offer the peoples of Indonesia and Sri Lanka a chance to reconnect with their history, reclaiming an integral part of their cultural heritage that was once taken away.