The art world is filled with fascinating stories, but few compare to modern history’s most significant art heist. On March 18, 1990, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston was the scene of a heist that left the world without thirteen masterpieces valued at over half a billion dollars. This article breaks down five surprising aspects of this famous theft that intrigue experts and art enthusiasts alike.

The Woman Behind the Museum

Isabella Stewart Gardner, the museum’s founder and namesake, was a fascinating character. As a philanthropist and art collector, Gardner built the museum to house her extensive collection. “When she opened the museum in 1903, she mandated that it be free of charge to gain the appreciation and attendance of all of Boston,” said Stephan Kurkjian, author of “Master Thieves: The Boston Gangsters Who Pulled Off the World’s Greatest Art Heist,” in an interview with CNN. Her museum was the most extensive private art collection in America then.

Gardner was also connected to the early women’s rights movement. The museum displays photographs and letters of her friend Julia Ward Howe, an organizer of two US suffrage societies, and a print of Ethel Smyth, a composer and close friend of English Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst.

The Art Not Taken

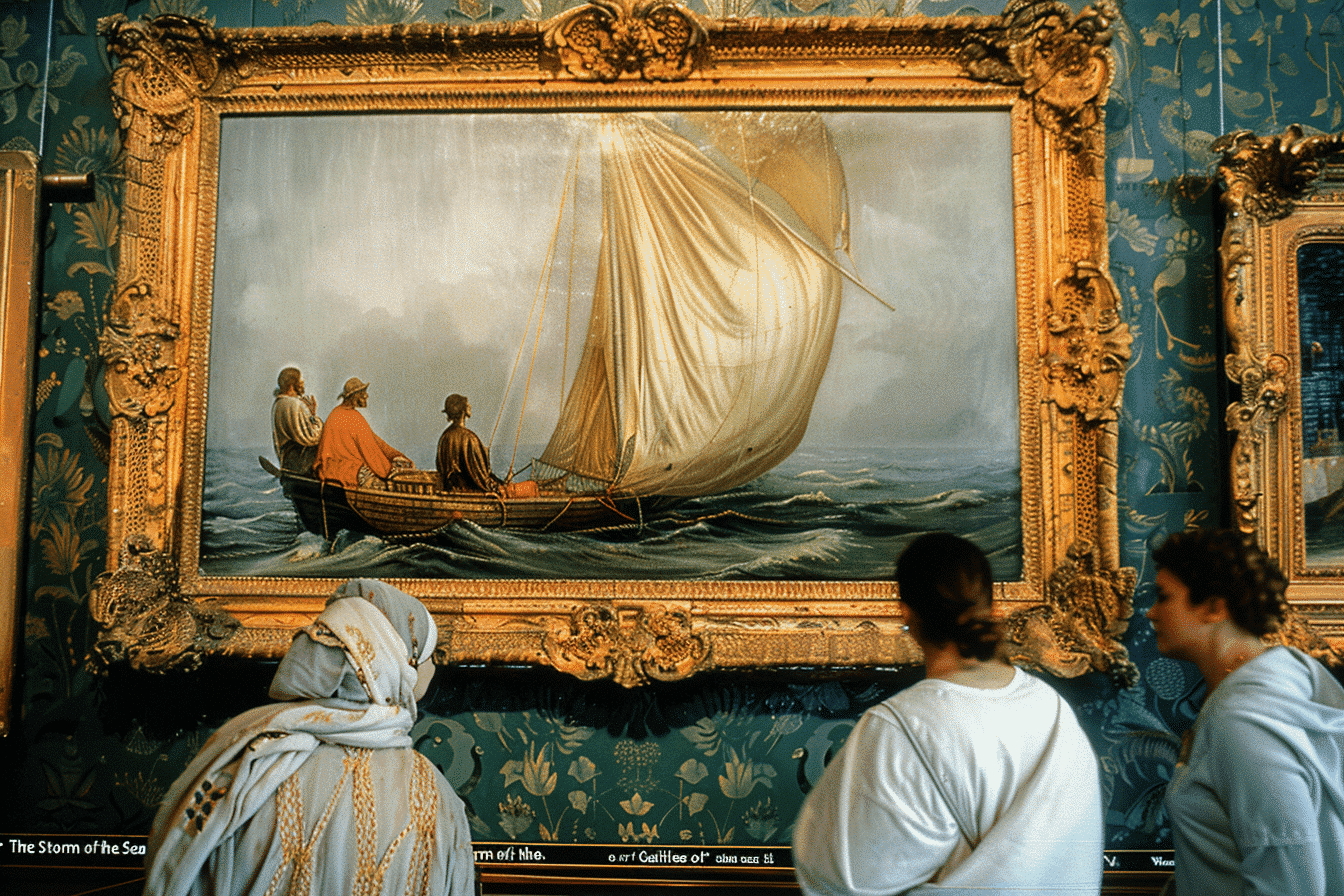

The thieves made off with art estimated to be worth over half a billion dollars, but they left behind the museum’s most expensive piece: “The Rape of Europa” by Titian. This painting, which Gardner bought in 1896 for a record price, might have been left due to its large size. The most significant artwork taken was Rembrandt’s “Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee,” measuring roughly 5×4 feet, whereas “The Rape of Europa” is nearly 6×7 feet.

The Napoleon Factor

Around 2005, the investigation into the stolen artworks took a surprising turn to Corsica, the Mediterranean island. Two Frenchmen with alleged ties to the Corsican mob attempted to sell a Rembrandt and a Vermeer. Former FBI Special Agent Bob Wittman was involved in a sting operation that fell apart when the men were arrested for selling art stolen from the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nice.

“It was sort of an odd choice for the thieves to take the Bronze Eagle Finial,” CNN correspondent Randi Kaye noted. “But it turns out that Corsica is essentially the homeland of Napoleon.” The Bronze Eagle Finial, a 10-inch ornament stolen from the top of a Napoleonic flag, hints at a deeper connection to Napoleon’s legacy.

A Rock’n’Roll Suspect

The heist was not the first time a Rembrandt was stolen from a Boston museum. In 1975, career criminal and art thief Myles Connor walked out of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts with a Rembrandt tucked into his coat. Although he was the FBI’s first suspect in the Gardner case, his incarceration at the time provided a solid alibi. Connor, who was also a musician, met Al Dotoli, who later helped him try to use a stolen Rembrandt to leverage a lesser sentence.

An Invisible Thief?

Édouard Manet’s “Chez Tortoni” was among the stolen artworks from the museum’s Blue Room. This theft is notable for two reasons: the painting’s frame was left not in the Blue Room but in the security office downstairs, and no motion detectors were set off in the Blue Room. “To even leave remnants of the paintings behind was savage,” remarked Kelly Horan, Deputy Editor of the Boston Globe. This unusual detail raised suspicions of an inside job. “At the FBI, we found that about 89% of museum institutional heists are inside jobs,” said Bob Wittman.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum heist remains one of the most intriguing unsolved art crimes. With its mix of fascinating characters, unexpected plot twists, and enduring mysteries, the heist continues to captivate the imagination of people around the world. As investigations and theories evolve, the hope remains that these priceless works of art will one day be recovered.