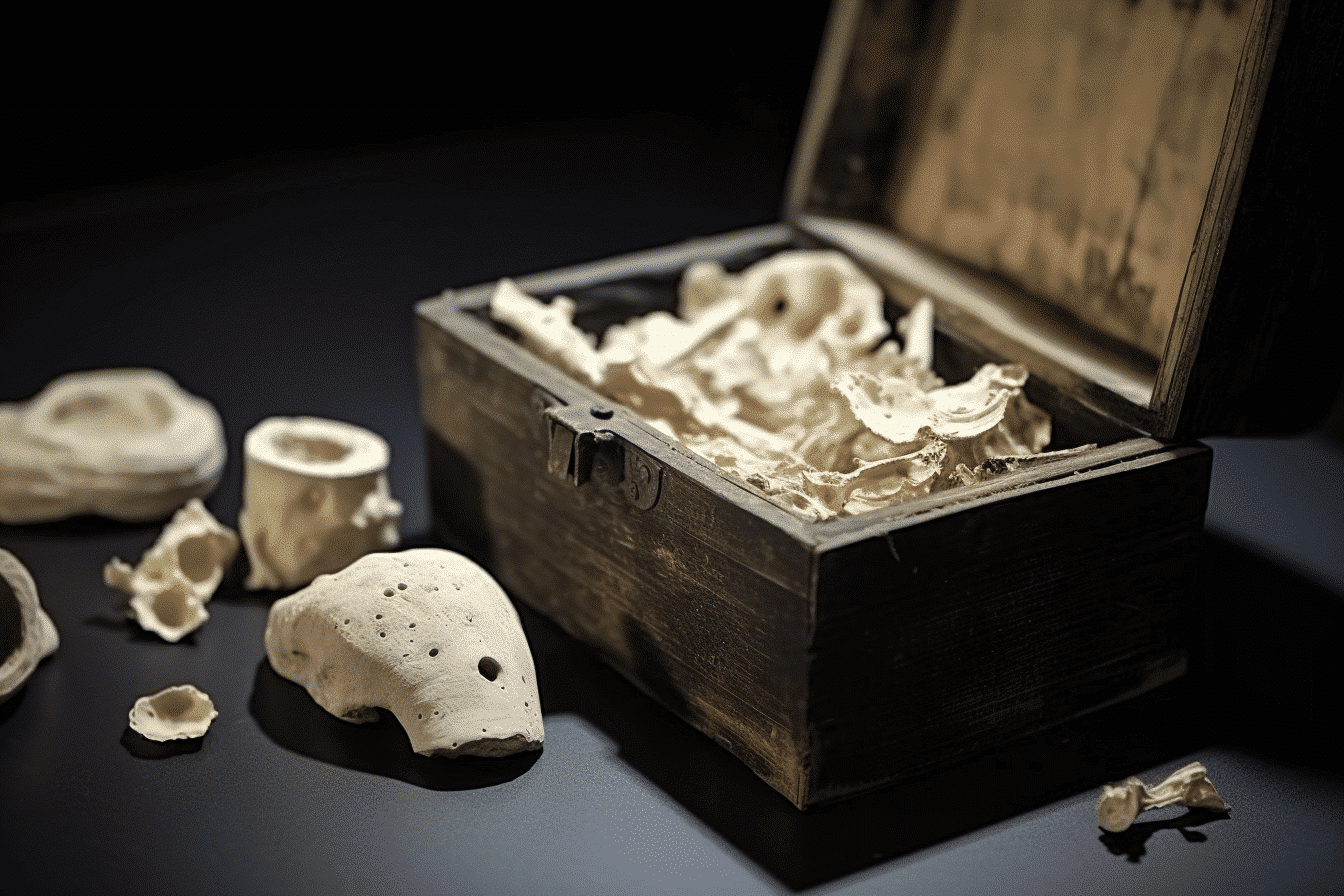

Bits of a skull, thought to belong to famed composer Ludwig van Beethoven, have been presented to an Austrian university following their lengthy stay in the United States.

The bone pieces were gifted to the Medical University of Vienna by an American entrepreneur, Paul Kaufmann. Kaufmann discovered them in a French bank’s safety deposit box upon his mother’s passing in 1990.

Subsequent investigations revealed that the bones, which were stored in a tin faintly marked with “Beethoven”, were obtained from his mother’s great-uncle’s estate, Franz Romeo Seligmann.

Seligmann, who passed away in 1892, was a medical historian, physician, and anthropologist in Vienna. He got possession of the skull fragments, now known as the Seligmann fragments, during an 1863 reburial of Beethoven’s remains for scientific examination.

Throughout his 56-year lifespan, Beethoven suffered from hearing loss, liver disease, and gastrointestinal issues.

In a letter penned to his brothers 25 years before his death, known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, Beethoven requested that his physician, Johann Adam Schmidt, disclose the nature of his illness posthumously.

In a telephonic conversation with CNN, Kaufmann, a retired entrepreneur from Carmichael, California, spoke about unexpectedly discovering the fragments when his mother passed away in France.

He stated, “There was a safety deposit box key in her purse. Upon opening it, my wife and I found, among other things, a small tin, and ‘Beethoven’ was inscribed on it.”

Years of scrutiny and investigations, supplemented by letters and documents discovered by Kaufmann, have since shown that Seligmann acquired the fragments when Beethoven’s body was exhumed in 1863. Beethoven’s final resting place is in Vienna’s Central Cemetery.

Kaufmann further explained, “My great-uncle was a professor of medical history with a specialization in skulls and anthropology because of his skull collection.”

Earlier this year, the journal Current Biology published a study in which researchers sequenced Beethoven’s genome for the first time, using DNA from preserved hair samples. These samples gave scientists valuable insights into Beethoven’s family history, chronic health issues, and potential causes of his death at 56.

Before the handover ceremony in Vienna, Kaufmann met with the researchers who studied Beethoven’s hair at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. The team has now taken DNA samples from the bones for analysis, which may take several months before they can link them to the hair samples.

Kaufmann expressed deep emotions about returning the fragments to their rightful place, where Beethoven is buried.

The Seligmann fragments will now be displayed in the Josephinum, the university’s museum. In expressing gratitude to Kaufmann for the donation, the university rector, Markus Müller, noted the museum’s relevance to the Beethoven narrative.

In a university press release, he stated, “We gratefully accept these fragments and will preserve them carefully. The Josephinum is the ideal location since Beethoven’s physician, Johann Adam Schmidt, was a professor here, and Beethoven himself wished for his illness to be studied posthumously.”

A 2005 Beethoven Journal academic paper reported that some of the composer’s bones were lost after a private autopsy.

Forensic pathologist Christian Reiter, based in Vienna, previously examined the skull fragments and judged them authentic. He was quoted in the press release as saying, “Further inquiries, such as DNA-based ones, will bring us closer to answering whether this is Ludwig van Beethoven. We are grateful to Mr. Kaufmann for returning these historical pieces to Vienna.”

Since Beethoven’s passing, there has been ongoing speculation about the exact nature of his illness and the cause of his death. In the final seven years of his life, the composer had at least two jaundice attacks associated with liver disease, leading to the popular belief that he died of cirrhosis.

Medical biographers have painstakingly gone through Beethoven’s letters, diaries, autopsy notes, physicians’ notes, and records from his body’s two exhumations in 1863 and 1888 to unravel his complex medical history.

Returning these fragments to Vienna could open new doors in uncovering the mysterious health issues of one of the world’s greatest composers, Ludwig van Beethoven. As we await the results from the DNA testing, the Medical University of Vienna holds an intriguing piece of history that may offer new insights into Beethoven’s life, struggles, and untimely death. What emerges could change the way we perceive not only Beethoven, but the intersection of art and human health, illuminating how remarkable creativity can still thrive even in the face of debilitating health challenges.