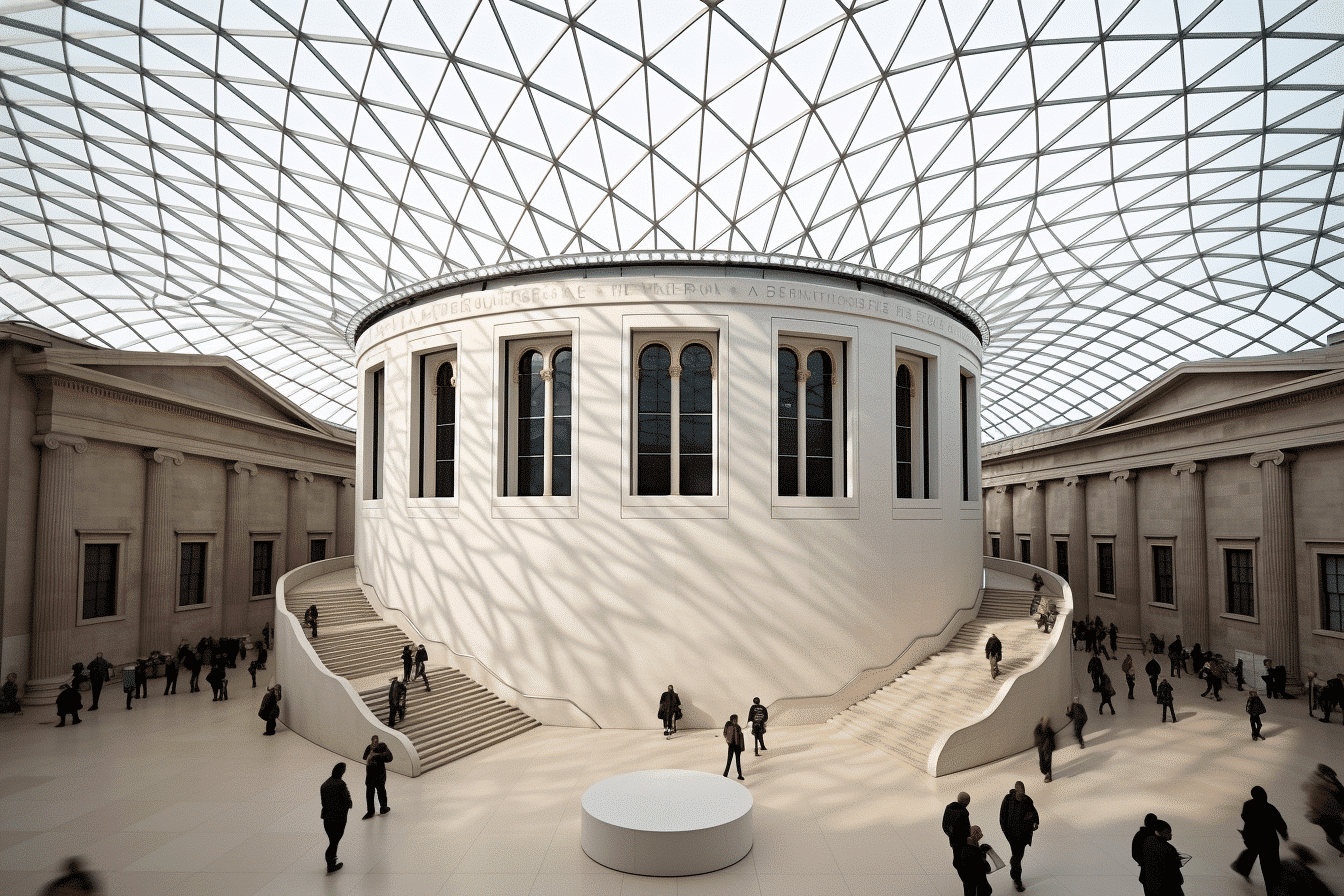

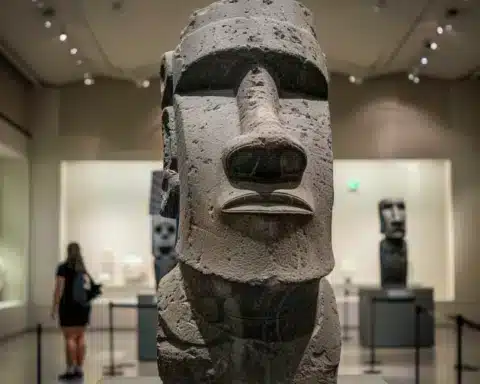

Last month, the British Museum unveiled its exhibition “China’s hidden century,” spotlighting 19th-century Chinese works, including poems by feminist and revolutionary Qiu Jin. However, the event sparked unexpected confusion for Yilin Wang, a writer and translator, when she started receiving perplexing messages from her colleagues.

According to a friend, the exhibit didn’t seem to have any credits for translators. Strangely enough, the English translations of Qiu Jin’s poems were strikingly similar to Wang’s. This led to whether Wang had been part of the exhibit.

In response, Wang clarified that the museum had not approached her, and her translations were used without permission, remuneration, or acknowledgement.

This incident stirred up a social media uproar, resulting in the British Museum releasing a statement confessing that Wang’s translations were used unintentionally, without permission and recognition.

While the Museum apologized to Yilin Wang for this oversight, it also removed her translations from the exhibition. They also offered to compensate her for the time her work was displayed, including the copies present in the printed catalogue.

Despite these actions, Wang believes the apology is inadequate and lacks sincerity, as she told CNN in a telephone interview. She accused the Museum’s statement of being too passive and evasive, failing to address broader ethical issues in academia, and overlooking the frequent marginalization of translators, especially women and individuals of colour.

The controversy initially flared up when Wang publicly criticized the British Museum’s use of her translations without consent or recognition on Twitter.

Wang’s Twitter thread, which has received nearly 53,000 likes and 15,000 retweets, alleges that the British Museum owes her for the unauthorized use of her translations, which were also featured in the museum’s online guide and printed catalogue.

In response, the British Museum asserted that they take copyright permissions seriously. Despite acknowledging the inadvertent mistake on this complicated project, they admitted falling short of their typical standards.

Despite the collaborative effort of over 400 people from 20 countries to put together the “China’s hidden century” exhibit, Wang was disappointed with her unnoticed exclusion from the project, especially considering the generous research grant it had received.

To Wang and other translation professionals, this incident underscores the systemic and persistent problem of translators’ work being disregarded or not acknowledged.

In response to this issue, the #NameTheTranslator social media campaign has been gaining momentum, urging publishers, educators, and reviewers to recognize translators and the original authors of literary works.

According to many translators, the omission of credit undermines the labour and skills required for effective translation, which requires years of training and cannot be achieved through simple automated translation tools.

Wang stressed the necessity of discussing copyright, recognizing translators’ labour, and taking preventative measures to avoid such incidents. She hoped the British Museum would engage with her earnestly and exhibit more remorse.

In this globalization era, translation’s importance cannot be overstated. However, incidents such as this highlight the vital need for proper recognition and compensation for translators. Their contribution to bridging cultural and linguistic gaps is invaluable, and their work should not be taken for granted. It’s clear that for real change to occur, institutions such as the British Museum need to lead by example and set higher standards for respecting the rights and acknowledging the hard work of translators.