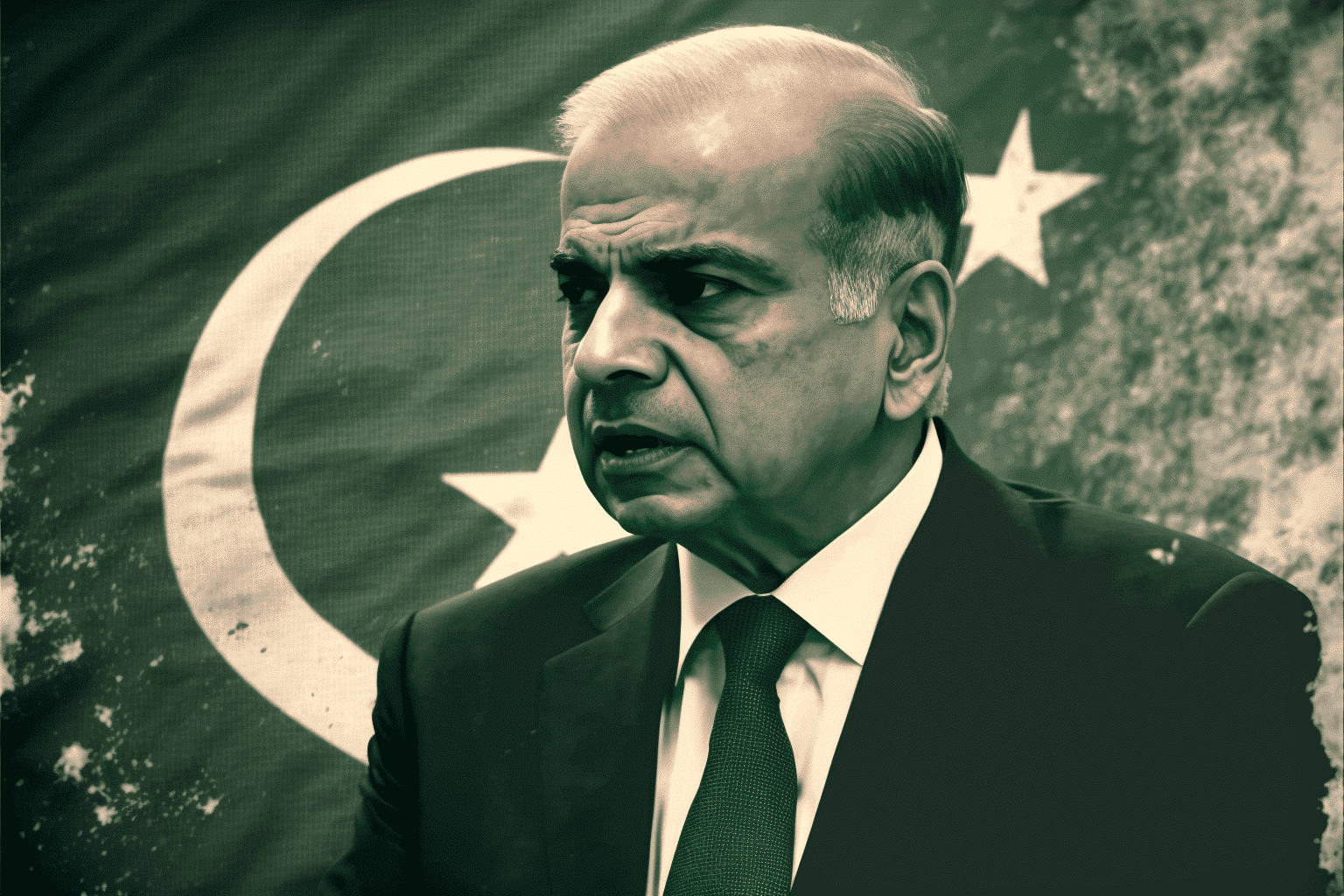

At the United Nations, Pakistan’s new prime minister had a brief chance to share the story of his nation’s struggles with floods and the impacts of climate change.

He used his brief opportunity on the world stage to speak about the pressing issue of floods and climate change affecting his nation, with over 33 million people at risk.

He was not alone in this endeavour, as every leader in attendance had a chance to craft a story about their nation and the world, hoping to grab the attention of others.

Storytelling is an inherent part of human nature. Even in a time of global politics and constant streams of information, the way a story is told, the details are chosen, and the delivery can make all the difference.

The advent of large-scale storytelling in recent years, with regular individuals being amplified globally alongside world leaders and industries dedicated to spreading disinformation, has made it increasingly difficult for even the most powerful voices to be heard.

Speaking at the UN in this current environment, where people often choose to believe what they want to believe, poses a significant challenge for leaders.

According to Evan Cornog, author of “The Power and the Story: How the Crafted Presidential Narrative Has Determined Political Success,” it is increasingly difficult to break through the noise and be heard.

He notes that in the past, there was more of a predisposition to listen to political leaders, but today, there is a tendency to see their words as propaganda and ignore them.

Despite the challenges, watching a week of speeches at the United Nations given by world leaders revealed that how a nation tells its story can be crucial in the attention economy, particularly for nations that are not currently in the spotlight.

Urgency was a common theme in the speeches, with leaders emphasizing the need for immediate action and the importance of the current moment.

Nepal’s foreign secretary, Bharat Raj Paudyal, stated, “we are living indeed in a watershed moment.”

Some speeches were more impactful than others, for example, Bhutan’s foreign minister Tandi Dorji read a letter from a child about the impacts of climate change, which made a strong impression on the audience.

Other speeches were more routine, some were simply a list of priorities, some were verbose and focused on old conflicts, and some were technical and detailed.

While some leaders have mastered the art of storytelling, others still need to. Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, for example, was given the unique opportunity to speak on video this year due to his status as a wartime president, which gave him certain advantages.

He was able to control the production values, re-record if he made a mistake, and use storytelling optics that have served him well since Russia’s invasion.

He utilized his trademark olive T-shirt and flag in the background and was able to dominate his own environment rather than being framed in the same green marble as everyone else.

Similarly, Ralph Gonsalves, the Prime Minister of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines gave a speech filled with metaphors and language that was highly noticeable and memorable. Some might consider it epic or grandiose, but it was effective either way.

“I ask the relevant and haunting questions: What’s new? Which world? And who gives the orders? The future of humanity depends on satisfactory answers to these queries,” Gonsalves exclaimed in his speech.

Storytelling goes beyond speeches, and some of the most memorable stories at the United Nations are told by leaders who went beyond words.

For example, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s famous shoe-banging incident at the 1960 General Assembly and Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi’s 1 hour and 36 minutes long angry speech at the United Nations before he ripped up a copy of its charter.

These speeches were not boring and were aimed at audiences different from a general international one.

The audience for a story told at the United Nations can vary, sometimes, it is intended for fellow leaders, sometimes for a specific leader, sometimes for a financial institution like the World Bank, and sometimes it is intended for a domestic media audience or for a neighbouring country.

Heads of state are still learning how to use this platform effectively to share their message, and not all are great storytellers, but with advancements in technology, those who are skilled at storytelling can thrive in this space.

One story that took a backseat this year at the United Nations was that of COVID-19, which was a dominant narrative at the 2020 all-virtual U.N. General Assembly and the hybrid 2021 edition.

However, this year it receded to a secondary story as other pressing issues, such as war, climate change, and food insecurity, took center stage.

This shift in focus reflected a global desire to move on and also a recognition that it was time to focus on other important stories.

Just outside the General Assembly building, a mockup of an outdoor classroom with pupil desks and backpacks was set up for a summit on transforming education, and every day, delegates walked past and saw these words etched on the blackboard: “Only one in three 10-year-olds globally can read and understand a simple story.”

This message highlighted the importance of storytelling, understanding them and casting a critical eye on them, which sit at the heart of 21st-century literacy. It is central to being a citizen, a smart consumer, and a leader.

It is also, as some say, a way station on the path toward what the United Nations covets most of all: peace.

In conclusion, storytelling plays a crucial role in the United Nations General Assembly, as world leaders use this platform to share their nation’s stories and struggles.

The art of storytelling has become more challenging in recent years with the advent of large-scale storytelling and disinformation. However, leaders skilled in this art can still effectively convey their message.

The audience for these stories can vary, and it is intended for fellow leaders, sometimes for a specific leader, sometimes for a financial institution, and sometimes for a domestic media audience or a neighbouring country.

The year 2021 had COVID-19 receded as a dominant narrative as other pressing issues such as war, climate change, and food insecurity took center stage.

However, it still serves as a reminder of the importance of storytelling in literacy and being a citizen, a smart consumer, and a leader.

The United Nations General Assembly serves as a platform for leaders to share their stories, and it is a crucial step toward achieving peace.