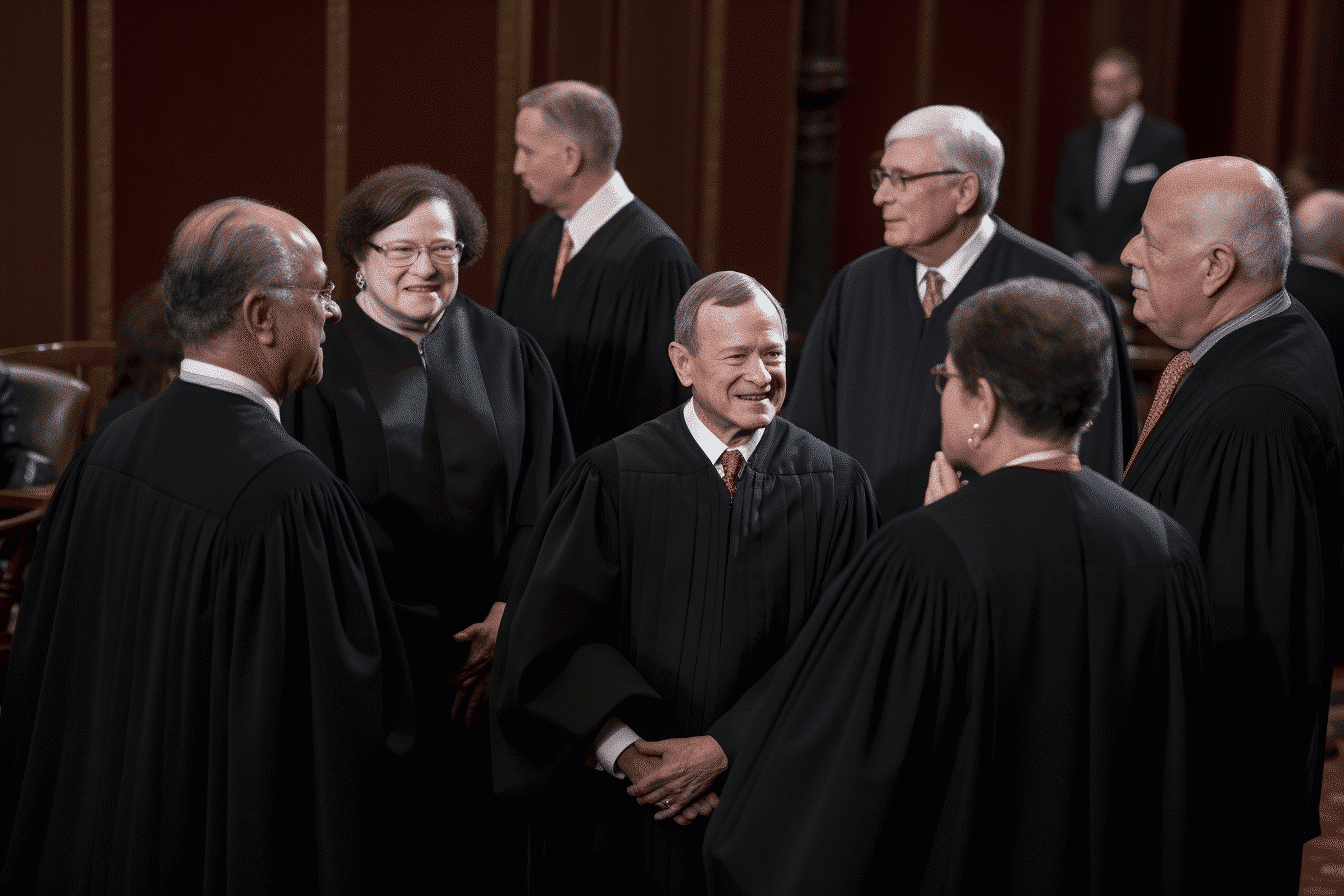

Shortly after the U.S. Supreme Court dismantled a significant part of the Voting Rights Act, legislators in Texas expressed intentions to enforce a rigid voter ID law previously hindered by a federal court. Concurrently, Alabama lawmakers declared plans to proceed with a similar law that had been stalled.

This verdict still echoes ten years later, as numerous Republican-led states establish voting limitations that, in many instances, would have required federal assessment if the predominantly conservative court had maintained the provision. Simultaneously, the Supreme Court continues to consider other lawsuits challenging elements of the historic 1965 law, initially rooted in the fierce fight for the voting rights of African Americans.

In the ensuing weeks, the justices are set to deliver a verdict on a new Alabama case that may substantially hinder minority groups’ ability to challenge gerrymandered political maps that weaken their representation.

“Once you reach that point, one must wonder what remains of the Voting Rights Act?” posed Franita Tolson, a constitutional and election law expert and co-dean of the University of Southern California School of Law.

Key elements of the act have been reauthorized with bipartisan agreement five times since then-President Lyndon Johnson signed it, most recently in 2006. However, congressional attempts to bridge the enforcement gap caused by the June 2013 Supreme Court decision—known as preclearance, a federal review of proposed election-related changes before implementation—have stalled amidst growing partisan disagreements over voting rights.

This recent influx of voting changes has been driven by Republican lawmakers, leveraging election concerns stirred by former President Donald Trump’s unfounded allegations of the 2020 election being rigged.

According to the Voting Rights Lab, which monitors state voting legislation, at least 104 restrictive voting laws have been passed in 33 Republican-controlled states since the 2020 election.

Alabama may soon add another law to this list, criminalizing assistance to non-family members in completing or returning an absentee ballot. While proponents argue the law’s necessity for enhanced security, critics argue that it could burden older, low-income, ill voters or those uncomfortable with the already demanding absentee ballot procedure, which includes the need to provide a photo ID copy.

“This is the epitome of voter suppression,” declared Betty Shinn, a 72-year-old African American woman from Mobile, who recently voiced her opposition to the bill during a legislative hearing in Montgomery. “It’s equivalent to asking me to guess the number of jellybeans in a jar or recite the Constitution from memory.”

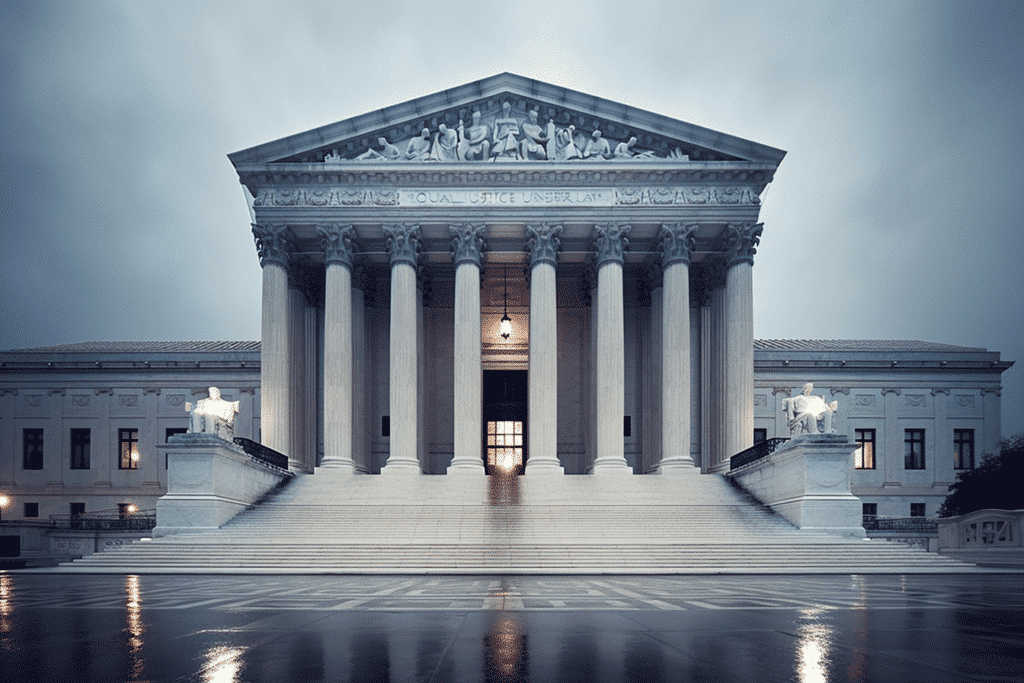

The Voting Rights Act was formulated to eliminate discriminatory practices rooted in the Jim Crow era. It utilized a formula to identify states, counties, and towns with a history of enforcing voting restrictions and low voter registration or participation. These jurisdictions were then mandated to submit any proposed changes in voting rules for prior review to either the U.S. Department of Justice or the federal court in Washington, D.C.

The legislation included provisions for jurisdictions to exit the preclearance requirement upon demonstrating particular improvements, and over the years, many have. As of the 2013 verdict, nine states and some counties and towns in six additional states were enlisted for federal review, including a handful of counties in California and New York.

Since the Supreme Court decision a decade ago, prompted by a case initiated by Shelby County, Alabama, lawmakers in the nine states previously subject to the preclearance requirement have passed at least 77 voting-related laws, as per the Voting Rights Lab analysis for The Associated Press.

Most of these laws enhanced voter access and likely passed federal review easily. However, at least 14 regulations – in Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia – implemented new voting restrictions, as the Voting Rights Lab found. Notably, nine prominent bills passed in the aftermath of the 2020 election would have likely attracted significant attention from the Justice Department.

Georgia’s Senate Bill 202 imposed ID requirements for mail voting, established the use of ballot drop boxes to limit the number permitted in metro Atlanta, and curtailed external groups from providing food and water to voters in line. While Republicans insist these changes bolster security, state groups have adapted their strategies to assist voters.

Arizona passed two laws last year that mandated voters use state and federal voter registration forms to prove their citizenship and purged voters based on county election officials’ suspicions about their citizenship or qualifications to vote.

Such measures could disproportionately impact Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities with culturally specific family names, according to Alexa-Rio Osaki, political director of the Arizona Asian American Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander for Equity Coalition.

“If the Shelby v. Holder case hadn’t occurred, we wouldn’t have to feel like we’re constantly excluded,” she remarked. “We’re essentially targeting our communities within the state merely based on whether our names appear American.”

In North Carolina, voting rights organizations anticipate reinstating the state’s rigid voter ID law by the new GOP majority on the state Supreme Court. They assert that this law will disproportionally affect younger voters. Several North Carolina counties, which house numerous historically black colleges and universities, were previously subject to federal review.

The Voting Rights Lab analysis identified three restrictive bills passed in North Carolina and two in Florida following the Shelby decision that would have necessitated federal review as they impacted local governments covered by the preclearance requirement.

Groups like Vote.org focused on voter registration and education at the state level, have had to promptly update website information, retrain volunteers, and revise educational resources to reflect the latest voting regulations and polling location details.

The organization has lodged legal challenges in Florida, Georgia, and Texas against new rules for registration forms that ban digital signatures.

“People fail to comprehend or fully acknowledge the rollback since the Shelby decision,” stated Vote.org CEO Andrea Hailey. “This implies that programs like ours must work twice as hard and incur greater costs to ensure everyone has the opportunity to vote.”

Without the pre-clearance process, the Justice Department and independent groups must depend on the courts to address potentially discriminatory laws after they have been enacted. While the legal system has measures to redress inflicted harm, elections are unique, said Justin Levitt, who recently served as the White House senior policy advisor for democracy and voting rights.

“You can’t reverse a discriminatory election,” Levitt observed, who held a top position at the Justice Department during the final years of the Obama administration. “The only possible legal remedy is to improve the subsequent election. However, in the interim, individuals elected in a discriminatory election are in office and formulating laws.”

In Texas, Republicans have instituted one of the country’s most stringent voter ID laws, restricted the usage of drop boxes, and redrawn political district maps to reinforce their overwhelming majority in the face of rapid demographic changes.

Legal challenges to Texas’ new voting laws persist, albeit with minimal effect. When a federal court 2019 ruled that Texas could continue to alter district maps unsupervised, it did so despite expressing “grave concerns” about the state where nearly nine out of every ten new residents are Hispanic.

Two years later, Democratic lawmakers held a 93-day walkout to protest additional voting restrictions that modified mail ballot regulations. These changes were hastily implemented before the 2022 midterm elections and resulted in the rejection of nearly 23,000 ballots.

“We’ve witnessed a drastic shift in election policy,” said Texas Rep. John Bucy, a Democrat. “I think all of this would be safeguarded if we had preclearance. We should collaborate to prioritize access to the ballot box, something we fail to do in this state.”

In addition to Texas, the Justice Department has filed legal challenges against new voting regulations implemented in Georgia and Arizona since the 2020 election.

Proponents of these laws maintain that even post-Shelby, courts remain an effectual check to redress problematic measures.

“Shelby County did not change the fact that state election laws that discriminate against protected groups like racial minorities are illegal,” asserted Derek Lyons, president and CEO of Restoring Integrity and Trust in Elections, an organization co-founded by Republican strategist Karl Rove. “And when courts have identified violations, they have promptly rectified them.”

In the 2013 decision, the Supreme Court majority held the formula for determining jurisdictions subject to preclearance as outdated and cited increased minority participation in voting.

It’s challenging to draw conclusions based on voter turnout data, especially since few states track it by race. An analysis of election and population data maintained by the AP shows that all but one of the nine states where a federal review was necessary before the court ruling saw a decrease in statewide voter turnout for the 2022 midterm elections compared with the previous midterms four years earlier — mirroring a national trend.

Some states implementing new restrictions also have voter-friendly election policies, like offering early voting and mail voting without an excuse.

“The Shelby opinion upholds the fundamental idea that if the federal government is to take the drastic step of overriding the constitutionally endorsed power of states to govern their elections, it must do so based on factual and current data,” stated Jason Snead, executive director of the Honest Elections Project. “By any objective measure, elections are free, fair, and accessible.”

Voting rights groups argue that this doesn’t necessarily imply voting is effortless, and they have responded to the restrictions with innovative strategies. For example, in Georgia, Common Cause established mobile printing stations nationwide so voters could comply with new voter registration rules requiring a physical signature on a printed form.

“Only through the efforts of all these communities and groups on the ground do voters have access,” said Sylvia Albert, the group’s national director of voting and elections. “But post-Shelby, courts are not recognizing the true damage these laws have caused.”

The Supreme Court further undermined another section of the Voting Rights Act two years ago with a ruling in a case from Arizona. It sided with the state in a challenge to new regulations that limited who could return early ballots for another person and barred votes cast in the wrong precinct from being counted. The conservative-majority court could further degrade voting rights meant to protect racial minorities in an Alabama case where the plaintiffs argue the state diluted the power of Black voters.

In Alabama’s Republican-drawn congressional map, only one of seven districts has a majority Black population in a state where over a quarter of the residents are Black. In this case, a broad ruling would not only uphold this map but also make it significantly harder to sustain claims of racial discrimination in redistricting across the country.

“If these kinds of things occur, they’ve effectively shut the door on the Voting Rights Act,” said Evan Milligan, executive director of Alabama Forward and the lead plaintiff in the case.

In Montgomery’s statehouse, Republican lawmakers pushing new mail ballot restrictions assert they are necessary to combat potential fraud, which is rare.

“The purpose of the bill is straightforward. It’s to ensure the election process in Alabama is as secure as possible,” said the bill’s sponsor, Republican Rep. Jamie Kiel.

During a legislative hearing in late May, Shinn, a woman from Mobile, testified that the bill threatens to criminalize volunteers like her at the League of Women Voters who assist those needing help with absentee ballots.

“I believe that the Voting Rights Act needs to be restored to its full strength,” Shinn said. “And until that happens, I have to keep fighting.”

As the debate rages on, it’s clear that the shadow of the Shelby decision continues to loom large over the landscape of American voting rights. Its visible and invisible effects are shaping the discourse around election laws, and until its ramifications are fully addressed, tensions are likely to continue. In the balance hangs not only the outcome of future elections but the very essence of the democratic process – equal access to the ballot box for all citizens.