Guatemala, a nation grappling with widespread corruption, has come under international scrutiny due to alleged governmental meddling in its presidential election. Despite President Alejandro Giammattei’s dwindling popularity domestically, his tight control over the justice system was barely challenged, barring sporadic reproofs from the United States and Europe.

This starkly contrasts the scenario just four years prior when Guatemala benefitted from a vigorous UN-backed anti-corruption initiative. However, since the expulsion of this mission by Giammattei’s predecessor, the president has systematically installed loyalists, displacing the prosecutors and judges who were champions of the anti-corruption drive. Even critics of the former anti-corruption fervour now agree that the country’s current state is significantly worse.

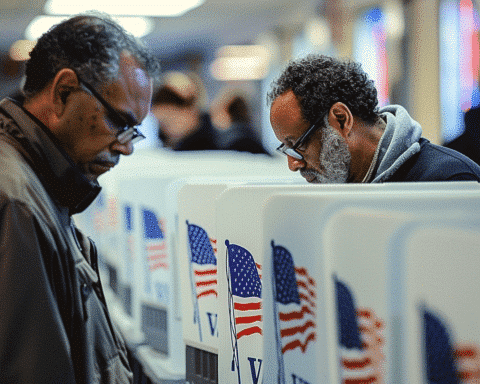

The presidential election on June 25th served as a jolt to Guatemalans and foreign observers. Anticipations of a runoff among candidates from the right and far-right were shattered when Bernardo Arévalo of the progressive Seed Movement secured the second position, fueled by numerous protest votes. Suddenly, the possibility of disrupting the status quo emerged for Guatemalans.

Katya Salazar, the executive director of the Due Process Foundation, opined that Arévalo’s unexpected backing indicated widespread dissatisfaction in Guatemala, which rattled the deeply-rooted power structure, including the president.

However, the Seed Movement was soon suspended on charges of breaching election laws, leading to a raid on the offices of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal shortly after the confirmation of the election results that placed Arévalo in the runoff.

This development provoked an immediate backlash, including from the United States, the European Union, the Organization of American States, various Latin American governments, and Guatemala’s most influential private business association. Sandra Torres, Arévalo’s conservative opponent in the runoff, announced her campaign suspension in solidarity, expressing that the playing field was not level.

While Torres’ UNE party has been instrumental in facilitating Giammattei’s legislative agenda, it seemed she felt the attack on the Seed Movement could compromise her candidacy. The Constitutional Court issued a preliminary injunction against the Seed Movement’s suspension, momentarily defusing the situation.

Despite not being legally eligible for re-election, Giammattei refrained from public appearances. His office released a statement asserting their respect for the separation of powers and non-interference in judicial matters.

Meanwhile, hundreds of protests erupted before the Attorney General’s Office. Protestors like Adolfo Grande, a 25-year-old repair technician, expressed their exhaustion from rampant corruption and desire for fair electoral processes.

Dinora Sentes, a 28-year-old sociologist and a Seed Movement supporter, said her protest was in defence of Guatemala and its urgent needs in areas like education and health rather than a single party.

Arévalo extended his gratitude to the Constitutional Court and the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, who pledged to uphold voters’ will against governmental intrusion.

“The corrupt individuals attempting to hijack these elections now find themselves sidelined,” he stated. “Today marks the first day of the campaign.”

As Guatemala enters a new chapter in its political journey, the world watches with bated breath. The recent presidential election interference allegations have thrust the nation’s longstanding corruption problems into the global spotlight, forcing Guatemalans to confront their country’s issues head-on. Amid the turmoil, there is a glimmer of hope that this could be a turning point for the Central American nation, leading to substantial changes in governance and a fight against corruption. As citizens rally behind their choices and voice their demands for a more transparent system, the outcome of this story could potentially influence the political landscapes of Guatemala and the wider Latin American region.