According to President Vladimir Putin, Russia relocated several short-range nuclear weapons to Belarus over the summer. This move, if true, brings these weapons closer to Ukraine and the boundary of NATO.

This proclaimed relocation of Russian arms into its neighbouring country, a faithful ally, signifies a new phase in Russia’s nuclear posturing amidst the Ukraine invasion. It is an additional attempt to discourage increased Western military aid to Kyiv.

Neither Putin nor his Belarusian counterpart, Alexander Lukashenko, revealed the number of weapons transferred. They only stated that Soviet-era facilities within Belarus were prepared for their storage and Belarusian missile crews and pilots had been trained in their operation.

The U.S. and NATO are yet to confirm this movement. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg condemned Moscow’s pronouncements as “dangerous and reckless,” stating earlier this month that there hasn’t been any observable change in Russia’s nuclear stance.

Although some experts question the claims by Putin and Lukashenko, others observe that it may be challenging for Western intelligence to track such movement.

Earlier this month, U.S. intelligence officials told CNN they had no reason to dispute Putin’s assertion about the initial delivery of the weapons to Belarus, acknowledging the difficulty for the U.S. in monitoring them.

Contrary to nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of obliterating entire cities, tactical nuclear weapons used against battlefield troops can yield as tiny as about one kiloton. The U.S. bomb dropped on Hiroshima during World War II was 15 kilotons.

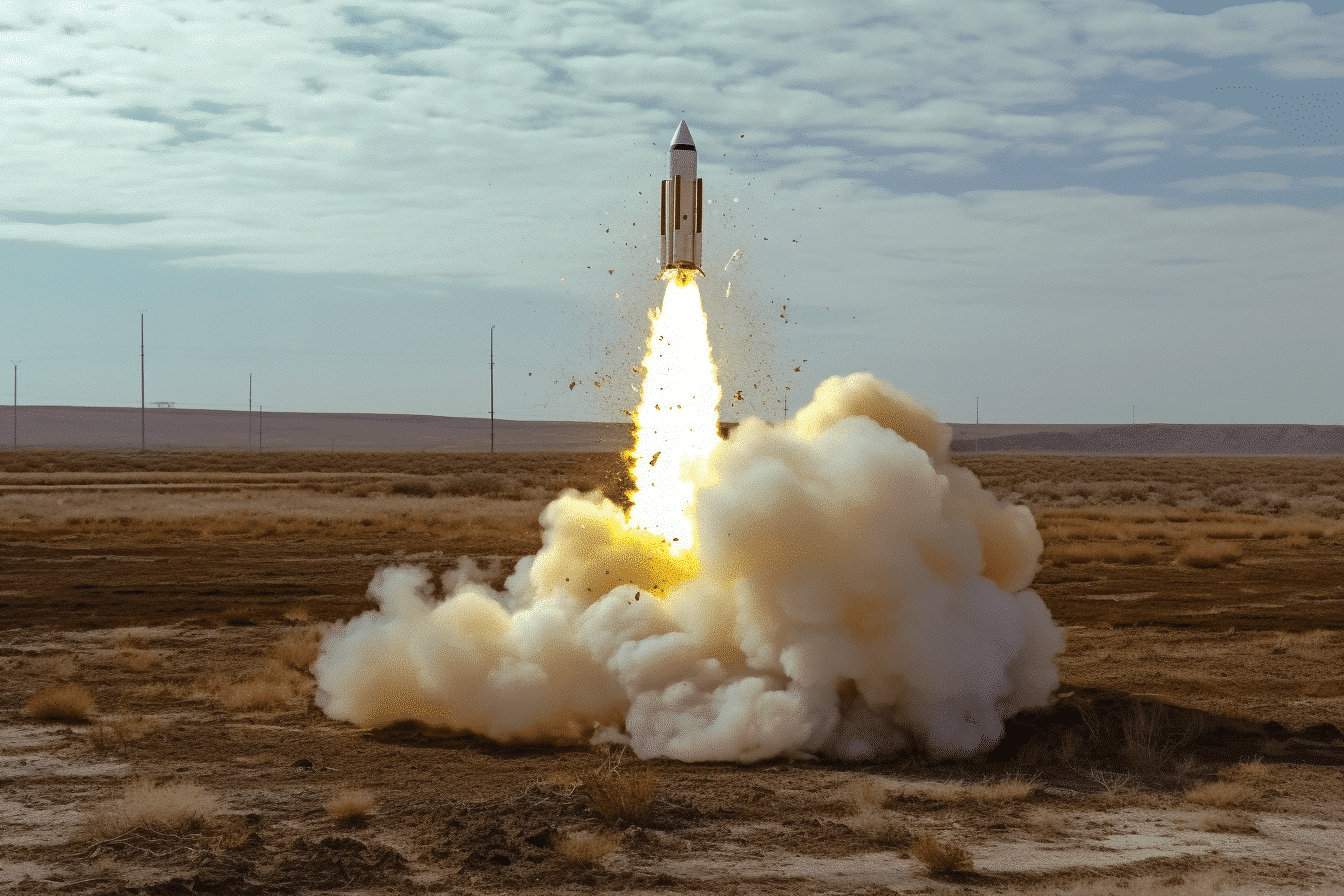

These devices, small enough to fit into bombs, missiles, and artillery shells, can be covertly transported on a truck or plane. Aliaksandr Alesin, a Minsk-based independent military analyst, indicated that the weapons, which use containers emitting no radiation, could have been secretly flown into Belarus without detection by Western intelligence.

Belarus possesses 25 underground Cold War-era facilities designed for nuclear-tipped intermediate-range missiles resilient against missile attacks, according to Alesin. Only five or six of these facilities could store tactical nuclear weapons, but all of them are in use to mislead Western intelligence.

Since the start of the war, Putin has often referred to his nuclear arsenal, vowing to use “all means” necessary to safeguard Russia. While he has moderated his rhetoric recently, a top lieutenant threatens nuclear use with chilling ease.

Due to Putin’s term limits, Dmitry Medvedev, the deputy head of Russia’s Security Council, who served as a placeholder president from 2008-2012, frequently warns that Moscow will not hesitate to deploy nuclear weapons.

Many Western observers regard these threats as empty rhetoric.

Keir Giles, a Russia expert at Chatham House, suggests that Putin has tempered his nuclear rhetoric in response to indications from China to do so.

Russia’s defence doctrine envisages a nuclear retaliation to an atomic strike or even a conventional weapons attack that “threatens the very existence of the Russian state.” This ambiguous phrasing has led Russian experts to suggest that the Kremlin specify those conditions more, thereby compelling the West to take the threats more seriously.

Sergei Karaganov, a top Russian foreign affairs expert and advisor to Putin’s Security Council, proposes that Moscow specify its nuclear threats to “break the will of the West” and compel it to halt its support of Ukraine.

Deploying nuclear weapons in Belarus was the first step, Karaganov said, possibly followed by a warning to ethnic Russians in countries backing Ukraine to evacuate areas near potential nuclear targets.

Meanwhile, the Moscow-based Council of Foreign and Defense Policies, which includes Karaganov among its top military and foreign policy experts, condemned his comments as a threat to all humanity.

While pro-Kremlin analysts are discussing these scenarios, Lukashenko, the Belarusian leader, maintains that hosting Russian nuclear weapons in his country serves as a deterrent against Polish aggression.

Giles, from Chatham House, believes the deployment is about “cementing Putin’s control over Belarus” and does not offer Moscow any military advantage compared to placing them in Russia’s Baltic exclave of Kaliningrad, which borders Poland and Lithuania.

Some observers question whether the transfer to Belarus has even occurred.

Belarusian military analyst Valery Karbalevich suggests that keeping such details concealed could be part of a Kremlin strategy of “applying permanent pressure and blackmailing Ukraine and the West.”

Alesin, the Minsk-based analyst, argues that the U.S. and NATO might be downplaying the deployment of nuclear weapons to Belarus due to the difficulty in countering such a threat.

The political opposition to Lukashenko warns that such a deployment turns Belarus into a Kremlin hostage.

Despite Lukashenko viewing these weapons as a “nuclear umbrella” safeguarding the country, exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who contested the 2020 election widely deemed fraudulent, warns that they make Belarus a target.

“We are telling the world that preventative measures, political pressure and sanctions are needed to resist the deployment of nuclear weapons to Belarus,” she stated, regretting the lack of a solid Western reaction so far.

The potential presence of Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus has raised tensions and increased uncertainty across the globe. Experts are divided on the authenticity of Putin’s claims, with some arguing that it could be a calculated strategy of intimidation against the West and Ukraine. Meanwhile, others assert that this could be a ploy to solidify Russia’s control over Belarus. As the world watches with bated breath, the situation underscores the importance of open dialogue, diplomacy, and strategic measures to ensure stability and prevent an escalation of conflict.