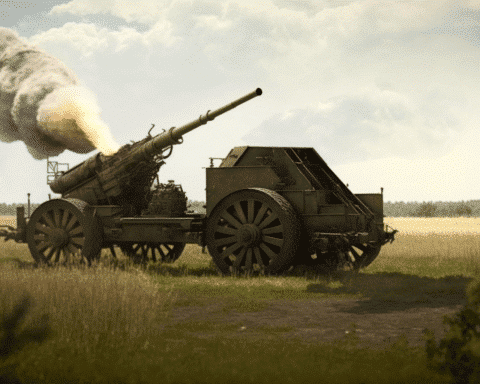

After a massive explosion rocked their small house in Ukraine’s Donetsk region, two children aged 9 and 10 attempted to pierce through the smoke-choked air.

The siblings called out for their father, but their pleas were met with an unsettling silence.

Subsequently, Olha Hinkin and her brother, Andrii, took shelter from the chaos as they had been trained. When the bombardment ceased and the smoke lifted, they discovered their father, lifeless and bloodied on their porch, a victim of a Russian missile attack.

Andrii, who now resides in the relatively safer city of Lviv near the Polish border, narrated the loss, “Our father was killed at seven in the morning.”

The Hinkin siblings are among the many Ukrainian children whose lives have been disrupted by the war. The full-blown Russian invasion has subjected them to relentless bombings, forcing millions to evacuate their homes and tragically orphaning many.

The conflict has claimed the lives of hundreds of children. For those who survive, the profound trauma is bound to cast long shadows on their adolescence and adulthood.

“Even if children escaped to a safer region, they haven’t forgotten their terrifying experiences,” observed psychologist Oleksandra Volokhova, who assists children who have managed to flee the violence.

The Ukrainian general prosecutor’s office reports that at least 483 children have died, and almost a thousand have been injured. Moreover, UNICEF estimates that about 1.5 million Ukrainian children are at risk of developing depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other psychological issues, which could have long-term implications.

According to the National Social Service of Ukraine, nearly 1,500 children have been orphaned. The highest number of child casualties is reported from Donetsk, the epicentre of numerous battles, where 462 children have been killed or injured, as per Ukrainian officials.

This number doesn’t include the casualties from Mariupol, also part of Donetsk province and currently under Russian occupation, where tracking casualties has proven challenging for Ukrainian authorities.

Before the conflict, the Hinkin family was like any other in the village of Torske, located just 35 kilometres (22 miles) from the front. The children were orphaned following the death of their father in October; they had lost their mother years before the war.

Half a year later, the siblings appear to be gradually overcoming their initial trauma.

Police and volunteers moved them to a safer region in western Zakarpattia, where they received support from government social services and the Ukrainian charity SOS Children’s Villages. The charity provided housing and counselling, offering the children security and hope.

Their story gained recognition in and around Torske after a heartrending video showing their father’s body being removed from their home was released by the police.

“We knew the village. We knew their house. We knew them,” shared Nina Poliakova, 52, from the nearby town of Lyman, who had also fled to Lviv with her family last year.

Despite her relocation, Poliakova kept herself updated about her hometown’s situation. Unfortunately, she also faced a personal tragedy when her 16-year-old foster son died suddenly due to a heart condition. She and her husband also cared for a foster daughter, whom they had taken in 2016 from the besieged town of Horlivka, where clashes with Russian-backed separatists had ignited years before the 2022 invasion.

During her grief, Poliakova received a call from a local children’s support center, asking her if she would meet the Hinkin siblings.

During their first meeting, they mainly spoke about their family home and their pets. Andrii especially enjoyed feeding the pigs.

Poliakova extended her family to include the two siblings, feeling a kinship with the children.

“We suffered a tragedy, and then fate brought us together,” Poliakova reflected. “There are so many children left alone, without parents. They need care and love. They long for comfort and support.”

Multiple organizations have emerged to help children navigate the trauma of war. One such group, Voices of Children, has fielded about 700 inquiries from parents seeking assistance for their children experiencing chronic stress, panic attacks, and PTSD symptoms.

As the war evolves, so do the pleas for help. This past winter, parents began seeking help for behavioural changes in their children, including apathy, aggression, anxiety, heightened sensitivity to loud noises, and anti-social tendencies.

“Children’s minds remain more adaptable than adults, and with prompt and quality support, we understand that a child can more readily overcome traumatic events,” commented Olena Rozvadovska, the head of Voices of Children.

Recuperating from living near combat lines was challenging for the siblings, admitted Poliakova.

“They were terrified,” she shared. Olha would cry and cling to her every time she heard the air-raid sirens, while Andrii appeared calm during the day but often woke up screaming at night.

A charity is known as Sincere Heart has been organizing short-term recovery camps for children and their mothers since the invasion began last year, offering a reprieve to over 8,000 individuals.

Eager to help restore their stolen childhood, Poliakova brought her three foster children to the camp. Here, they played with other children who shared similar experiences and participated in art sessions, dance classes, and other therapeutic activities designed to help children express their emotions.

The camp, filled with children from war-torn regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, and other areas, was a symphony of laughter and playfulness. Many of these children had witnessed bombings, suffered the loss of a parent, or were recovering from war-inflicted injuries.

The children were encouraged to express their feelings by drawing on white T-shirts during an art session. Many depicted the blue and yellow of the Ukrainian flag and inscribed the phrase “Glory to Ukraine.”

Olha Hinkina drew a heart in the colours of the national flag.

“Children project what’s most apparent to them,” Rozvadovska noted. “They are growing amidst the colours of our flag, daily updates from the front line, and a sense of pride for the army.”

She believes recovery is attainable for these children, who may grow stronger through survival.

“These experiences have taught them survival skills,” she asserted. “Perhaps it has even made them more resilient and adaptable.”

When Andrii Hinkin recalls his hometown, he chooses to remember it as a beautiful village, not as a war zone scarred by bombings and explosions.

Asked about his dreams for the future, he responds shyly. “I want to grow up.”

In the face of adversity and upheaval, the Ukrainian children’s and their caregivers’ strength shines through. Their resilience and adaptability, tested by war, promise recovery and rebuilding. Despite the unimaginable horrors they’ve witnessed, they’re determined to regain their lost innocence, reclaim their disrupted childhood, and continue to dream. As they look toward a future beyond the bombings and loss, their most profound wish is simple and universal: to grow up.